Translate this page into:

Urodynamic profile in acute transverse myelitis patients: Its correlation with neurological outcome

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to observe urodynamic profile of acute transverse myelitis (ATM) patients and its correlation with neurological outcome.

Patients and Methods:

This prospective study was conducted in the neurorehabilitation unit of a tertiary university research hospital from July 2012 to June 2014. Forty-three patients (19 men) with ATM with bladder dysfunction, admitted in the rehabilitation unit, were included in this study. Urodynamic study (UDS) was performed in all the patients. Their neurological status was assessed using ASIA impairment scale and functional status was assessed using spinal cord independence measure. Bladder management was based on UDS findings.

Results:

In total, 17 patients had tetraplegia and 26 had paraplegia. Thirty-six patients (83.7%) had complaints of increased frequency and urgency of urine with 26 patients reported at least one episode of urge incontinence. Seven patients reported obstructive urinary complaints in the form of straining to void with 13 patients reported both urgency and straining to void and 3 also had stress incontinence. Thirty-seven (86.1%) patients had neurogenic overactive detrusor with or without sphincter dyssynergia and five patients had acontractile detrusor on UDS. No definitive pattern was observed between neurological status and bladder characteristics. All patients showed significant neurological and functional recovery with inpatient rehabilitation (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Conclusions:

The problem of neurogenic bladder dysfunction is integral to ATM. Bladder management in these patients should be based on UDS findings. Bladder characteristics have no definitive pattern consistent with the neurological status.

Keywords

Acute transverse myelitis

neurogenic bladder

neurological and functional recovery

urodynamic study

Introduction

Acute transverse myelitis (ATM) is an inflammatory disorder of spinal cord with varying etiopathology.[123] It is characterized clinically by acutely or subacutely developing symptoms and signs indicative of spinal cord pathology with neurologic dysfunction of motor, sensory, and autonomic nerves and nerve tracts. Spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and lumbar puncture often show evidence of acute inflammation. At nadir, approximately 50% of patients have loss of all movements of their legs, virtually, all have bladder dysfunction, and 80–94% of patients have sensory symptoms in the form of numbness, paresthesia, or band-like dysesthesias.[4567] It may be a clinically isolated syndrome presenting as the initial manifestation of multiple sclerosis.[891011]

Bladder involvement is commonly observed in patients diagnosed with ATM both in pediatric and adult population, but scanty literature is available about its correlation with neurological outcome and severity of the lesion.[121314151617] Bladder dysfunction could be one of the most disabling sequelae and shows variable recovery even in cases with complete neurological recovery.[13] The patients may complain of increased frequency, urgency, urge incontinence, or there could be complaints of incomplete evacuation of bladder or straining to void.[18] The patients start to recovery after 2–12 weeks of onset of illness and continue to do so for up to 2 years. Nearly, two-third of the affected patients have significant bladder and bowel disturbances along with poor sensory-motor recovery with remaining one-third showing good recovery in all domains.[18]

This prospective study was conducted with the aim to assess the neurogenic bladder dysfunction in patients with transverse myelitis by performing urodynamic study (UDS) and managing bladder based on the findings. We also attempted to observe the correlation between bladder characteristics and level, severity of spinal cord lesion as well as the functional outcome of inpatient rehabilitation.

Patients and Methods

This prospective study was conducted in the Department of Neurological Rehabilitation of a University tertiary research hospital between July 2012 and June 2014. The diagnosis of ATM was made in the department of neurology after the patients fulfilled the clinical, diagnostic laboratory work-up and imaging criteria.[4] The patients diagnosed with transverse myelitis with neurogenic bladder dysfunction (all ATM patients had neurogenic bladder dysfunction) with varying urinary complaints, who were admitted to the department of inpatient rehabilitation, were included in the study. The project was approved by the Institute's Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from all the patients before recruitment in the study. The patients with first episode of transverse myelitis and clinical picture of tetraplegia or paraplegia (complete and incomplete) with bladder dysfunction were included in the study. The patients with presence of brain demyelination (confirmed with MRI scan), patients who were positive for neuromyelitis optica (NMO) spectrum disorders (confirmed with aquaporin-4 antibody test), and patients with recurrent transverse myelitis were excluded from the study.

The detailed clinical and neurological examination was done for all the patients after admission. Their neurological status and recovery (admission and discharge) were recorded using the ASIA impairment scale (AIS).[19] Functional status and recovery were assessed using Barthel Index (BI) and spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) both at admission and discharge.[2021]

All the patients were out of spinal shock like picture before being enrolled for the urodynamic procedure. They were on clean intermittent catheterization/self-voiding before the procedure. UDS (Filling and voiding cystometrography) was performed using multichannel pressure recording technology with Life-Tech (USA) equipment, Primus. Filling cystometry was performed with the patients in the supine position on the urodynamic table. Bladder filling was done with normal saline at medium fill rate (10–50 ml/min) and varied from patient to patient. The patients were made to sit during voiding phase to void urine. Recordings were made during the procedure (both filling and voiding phase). Sphincter electromyography was performed in all patients to observe sphincter activity and possible synergic/detrusor sphincter dyssynergia pattern. It was done using anal patch surface electrodes. The complete data were captured by the software. The analysis of graph and values of relevant pressures was done, the final urodynamic diagnosis was made, and management determined and instituted consisting of pharmacotherapy, supportive and behavioral measures.[14]

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical package for social science SPSS version 17.0 (IBM, IL, Chicago, USA). Descriptive statistics included frequency, mean, and standard deviation for quantitative variables such as age, duration of illness, duration of stay, BI, and SCIM scores. Paired Student's t-test was used for the assessment of functional recovery using mean BI and SCIM scores at admission and discharge. The Wilcoxon nonparametric test was used for the assessment of neurological recovery by comparing admission and discharge ASIA scale scores. Spearman correlation coefficient test was used to observe a correlation between detrusor characteristic and neurological and functional recovery. Statistical significance was considered at P <0.05.

Results

A total of 43 patients meeting the criteria were included in the study (19 males, 24 females). The mean age was 30.1 years ± 15.3 (range 10–69 years). The median duration of illness at admission in the rehabilitation ward was 28 days (range 22–921 days). The mean length of stay in the rehabilitation unit was 32.6 days ± 17.2 (range 6–78 days). The patient distribution based on clinical presentation was as follows: Tetraplegia in 17 (39.5%) and paraplegia in 26 (60.5%).

Thirty-six patients (83.7%) had complaints of increased frequency and urgency of urine with 26 patients had reported at least one episode of urge incontinence. Seven patients reported obstructive urinary complaints in the form of straining to void with 13 patients reported both urgency and straining to void.

Bladder characteristics based on UDS findings are mentioned in Table 1.

More than 86% patients (37/43) had overactive detrusor (OAD) with or without dyssynergia and 27 patients (62.8%) were put on anticholinergic medications. One patient had normal UDS and was advised voluntary micturition. Forty-two patients (97.7%) were advised timed clean intermittent catheterization as behavioral and supportive measures to manage neurogenic bladder. Besides, three patients had complaints of stress incontinence and were advised adrenergic agonists to control leaks.

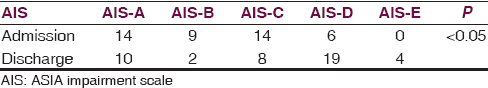

The patients showed significant improvement in neurological status with inpatient rehabilitation (assessed using AIS). Thirty-one patients (72.1%) in the study were AIS-C, D, or E at the time of discharge showing significant recovery.

The neurological status of the patients at admission and discharge is mentioned in Table 2.

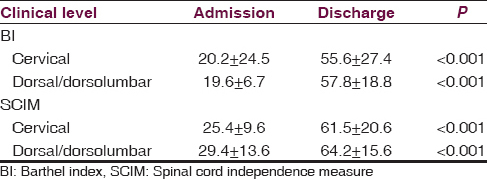

Similarly, the patients also showed significant functional recovery with inpatient rehabilitation irrespective of the level of myelitis. Functional recovery of the patients assessed using BI and SCIM scores is mentioned in Table 3.

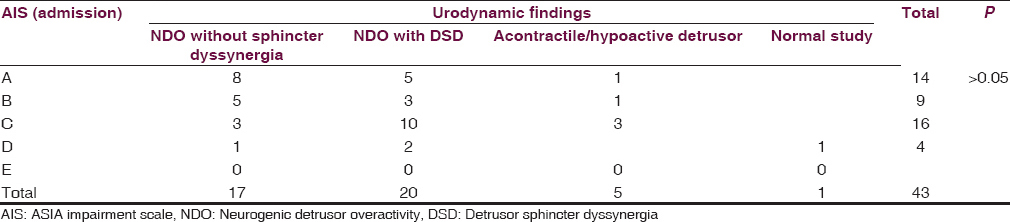

Correlation between the neurological status of the patients (using admission AIS) and urodynamic findings is mentioned in Table 4.

Majority of patients with AIS-C had detrusor sphincter dyssynergia are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Bladder dysfunction is an integral part in majority and could be the presenting symptom of transverse myelitis.[12] Its management is important to prevent recurrent urinary tract infection, preserve renal function, and manage urinary incontinence.[18] Most of the patients in the present study were admitted to the neurorehabilitation unit in the subacute phase of illness. Only six patients admitted after 3 months of illness, and in fact, two patients reported in the 3rd year of their illness without being investigated for their bladder issues in the past. Most of the patients (37/43) had OAD on UDS study, with or without dyssynergia. This observation is contrary to some of the earlier studies reporting acontractile/hypoactive detrusor as predominant finding.[151722] The difference could be the duration of illness. In our study, UDS was performed only when the patients were out of spinal shock like picture and started reporting urinary complaints such as increase frequency/urgency or after 4-6 weeks of illness. During the initial phase, the patients have the inability to void with urinary retention as a predominant complaint. UDS performed at this stage would probably show acontractile/hypoactive detrusor in the majority of cases. As with other myelopathies, UDS performed after 4–6 weeks of initial insult would give more accurate status of bladder dysfunction and help in managing bladder better in the long term. Our experience with nontraumatic myelopathies yielded similar results in the past.[1416]

The diagnosis of transverse myelitis was made in the Department of Neurology with usual tools such as MRI scans and cerebrospinal fluid examination. In the rehabilitation unit, we ensured that the patients with similar MRI findings but positive for aquaporin-4 antibodies (NMO) are excluded from the study. Similarly, the patients with brain demyelination (suggestive of Multiple Sclerosis or Acute Demyelinating Encephalomyelitis) were excluded from the study. This ensured a homogeneous population of transverse myelitis patients included in the study.

Overwhelming number of patients in the study had neurogenic OAD, with or without sphincter dyssynergia. Interestingly, no consistent pattern was observed between the neurological status of the patients (AIS) with bladder characteristics according to UDS. The present study shows the importance of performing UDS in all ATM patients for the management of micturition issues, irrespective of the extent of sensory-motor recovery as patients might continue to have urinary complaints in spite of being independent in performing other activities of daily living including locomotion. These findings are consistent with earlier work by Ganesan and Borzyskowski.[12] They also observed an insignificant correlation between motor recovery and urinary symptoms in patients with myelitis. However, in another study by Leroy-Malherbe et al., with pediatric transverse myelitis patients, authors observed a positive correlation between early motor recovery and improvement in bladder symptoms.[23] Authors also proposed that routine video urodynamic studies in children presenting with acute TM could help in delineating the problems and guide early management. In the present study, four patients had a complete recovery and were ASIA E at the time of discharge. Only one of these patients had normal UDS and remaining 3 had OAD and were advised management based on findings. These observations again emphasized the fact that the patients with transverse myelitis might show complete neurological recovery but bladder could still behave abnormally and their bladder should be managed based on UDS findings.

The patients showed significant functional recovery as can be seen with BI and SCIM scores (admission vs. discharge – P < 0.001). This recovery was irrespective of topographical presentation of the patients (Tetraplegia and paraplegia). This is not unusual and has been amply documented with most of the nontraumatic myelopathy rehabilitation studies.[141524252627] Similarly, the neurological status showed significant improvement when admission scores were compared with discharge scores (P < 0.05).

There are limitations to this study such as small sample size and lack of follow-up both in terms of functional and neurological recovery and long-term bladder behavior (repeat UDS). However, the strength of the study is a homogeneous population with ruling out other causes of demyelination and performing UDS after sufficient gap since insult, so the bladder could be managed in most patients for a long duration.

Conclusions

This prospective study suggests neurogenic bladder dysfunction as an integral part of transverse myelitis. UDS should be performed once the patient is out of spinal shock like picture to have more relevance and long-term management of the bladder can be determined. We observed significant functional and neurological recovery in these patients with inpatient rehabilitation; however, there was no correlation between neurological status and bladder characteristics in these patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: Complete recovery after intravenous immunoglobulin. Hippokratia. 2012;16:283-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute myelopathies: Clinical, laboratory and outcome profiles in 79 cases. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 8):1509-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transverse myelitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1483-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2002;59:499-505.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transverse myelitis. Retrospective analysis of 33 cases, with differentiation of cases associated with multiple sclerosis and parainfectious events. Arch Neurol. 1993;50:532-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical course and long-term prognosis of acute transverse myelopathy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;81:431-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- A clinical, MRI and neurophysiological study of acute transverse myelitis. J Neurol Sci. 1996;138:150-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute transverse myelitis with normal brain MRI: long-term risk of MS. J Neurol. 2008;255:89-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospective study of patients presenting with acute partial transverse myelopathy. J Neurol. 2003;250:1447-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute partial transverse myelitis with normal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging: transition rate to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:373-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: outcome and conversion to multiple sclerosis in a large series. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and course of urinary tract dysfunction after acute transverse myelitis in. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:473-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neurogenic bladder following myelopathies: Has it any correlation with neurological and functional recovery? J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014;5(Suppl 1):S13-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bladder dysfunction in acute transverse myelitis: magnetic resonance imaging and neurophysiological and urodynamic correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:154-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urodynamic profile of patients with neurogenic bladder following non-traumatic myelopathies. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:42-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urodynamic evaluation and rehabilitation outcomes in transverse myelitis. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2009;14:37-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury (revised 2011) J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- A multicenter international study on the spinal cord independence measure, version III: Rasch psychometric validation. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:275-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Troubles sphinteriens de la myelopathie aigue transverse de l’enfant. Aspects diagnostiques, pronostiques, reeducatifs. Arch Pediatr. 1998;5:497-502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recovery of neurologic function following nontraumatic spinal cord lesions in Israel. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2278-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traumatic vs non-traumatic spinal cord lesions: comparison of neurological and functional outcome after in-patient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:482-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urodynamics findings in transverse myelitis patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: Results from a tertiary referral urodynamic center. Neurourol Urodyn 2015 doi: 10.1002/nau. 22930 Epub ahead of print

- [Google Scholar]

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction affect quality of life. A cross sectional study of 60 patients with aquaporin-4 antibody positive Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:614-8.

- [Google Scholar]