Translate this page into:

Classical case of late-infantile form of metachromatic leukodystrophy

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

We would like to share a rare case of late-infantile form of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) presenting in our institution.

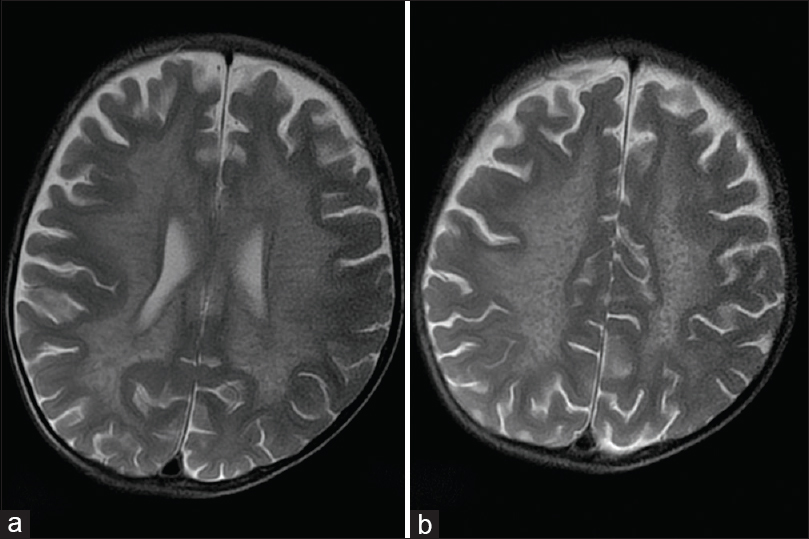

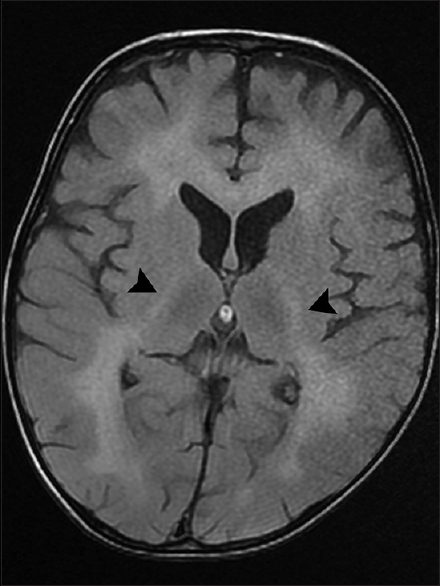

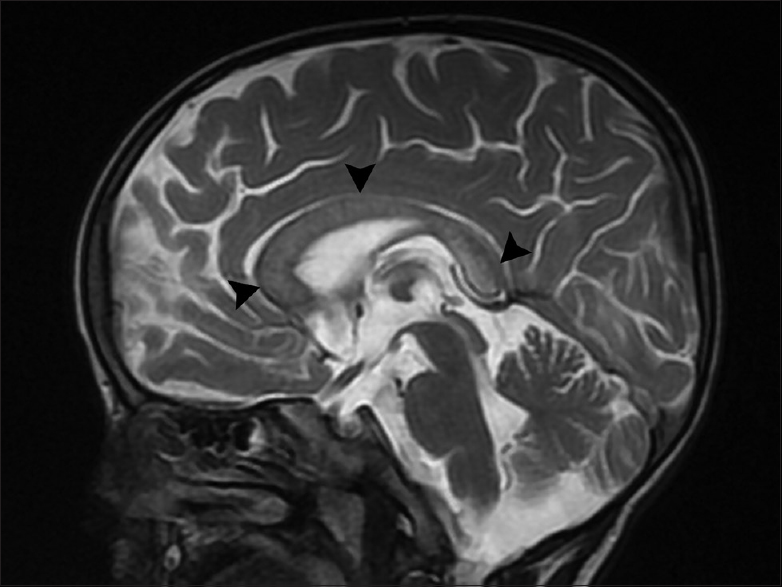

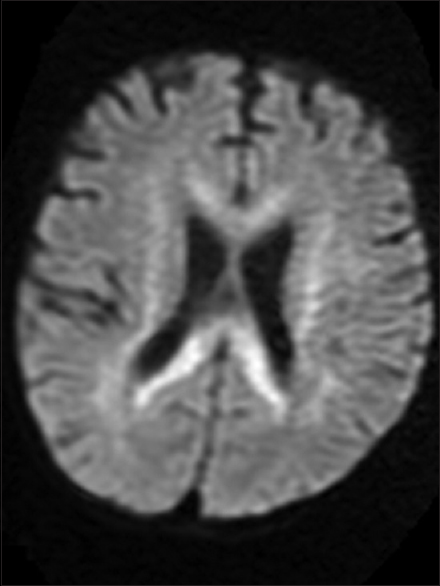

The parents of a 3-year-old boy reported in the pediatric outpatient department and gave a history of progressive psychomotor regression, disturbance of gait, and quadriplegia in their son for the last 1 year. The patient was admitted for workup, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain was performed the next day. The MRI scan revealed confluent T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities in the periventricular white matter and centrum semiovale with linear and dot-like hypointensities within it characteristic of the “tigroid” and “leopard skin” appearance of demyelination [Figure 1a and b]. The posterior limb of internal capsule and the corpus callosum (genu, body, and splenium) were also involved [Figures 2 and 3]. The diffusion-weighted images revealed restriction in the periventricular white matter and corpus callosum [Figure 4]. The peripheral U fibers were spared, and no noticeable enhancement was seen in postcontrast images. In combination; the clinical and imaging findings were suggestive of late-infantile form of MLD. The diagnosis was confirmed biochemically by the reduced arylsulfatase A levels in peripheral white blood cells and 24 h urine assay.

- Magnetic resonance imaging axial T2-weighted images show the classical hypointense stripes and dots within the demyelinated white matter giving a “tigroid” appearance in the periventricular white matter (a) and the “leopard skin” appearance superiorly in the centrum semiovale (b)

- Axial T2-fluid attenuated inversion recovery image demonstrates a hyperintense signal in the posterior limb of internal capsule on both sides (arrowheads)

- Midsagittal T2-weighted image shows the involvement of corpus callosum (arrowheads)

- Axial diffusion-weighted image demonstrates restriction within the involved corpus callosum and periventricular white matter

MLD is a form of lysosomal storage disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance which occurs due to deficiency of arylsulfatase A enzyme resulting in accumulation of sulfatides in the peripheral and central white matter.[1] The prevalence of MLD is about 1 in 100,000 newborns[2] and according to age, three forms have been described: Late-infantile, juvenile, and adult. Infantile form is the most common, manifesting at 12–18 months of age with regression of motor development, intellectual decline and disturbances of speech/gait, and blindness.[12] MRI findings of MLD include symmetric confluent hyperintense areas in periventricular white matter with a demonstration of “tigroid” or “leopard skin” pattern in deep white matter.[3] The radially oriented hypointense stripes or dots which give the tigroid/leopard skin appearance have been related to relative sparing of myelin in the perivenular region.[4] Diffusion-weighted MR imaging reveals restricted pattern of cytotoxic edema in the affected white matter in the absence of ischemia, the cause of which is probably due to restricted mobility of water molecules in the abnormal myelin.[5] Subcortical U-fiber sparing is characteristically seen in initial stage, but involvement may occur in later stages.[2] There may also be variable involvement of corpus callosum, corticospinal tract, and cerebellar white matter.[1] In postcontrast MR either no enhancement or punctate foci of enhancement can be seen in the background of nonenhanced demyelinated white matter.[12]

Apart from MLD, tigroid appearance can also occur in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, but differentiation is usually possible based on the clinical context and low levels of arylsulfatase A in the peripheral white blood cells and urine in the former.

Prognosis in MLD is not good with progressive quadriplegia, decerebration, and death within 6 months to 4 years after onset.[1]

Our case is thus illustrative of the late-infantile form of MLD and showed typical clinical and MR imaging findings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leukodystrophy in children: A pictorial review of MR imaging features. Radiographics. 2002;22:461-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR of childhood metachromatic leukodystrophy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:733-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histopathologic correlates of radial stripes on MR images in lysosomal storage disorders. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:442-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metachromatic leukodystrophy: Diffusion MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1424-6.

- [Google Scholar]