Translate this page into:

Labyrinthitis ossificans after meningitis: Superiority of high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging in demonstration of disease extent compared to high-resolution computed tomography

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Labyrinthitis ossificans after meningitis is a cause of sensorineural hearing loss in children. We discuss a case of an adolescent male with sensorineural hearing loss and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated the extent of the labyrinthitis ossificans much better than high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). A 14-year-male presented with a history of profound bilateral sensorineural deafness. He had pyogenic meningitis 6 months earlier with Streptococcus pneumoniae as causative agent. MRI done at that time revealed leptomeningeal enhancement in basal cisterns and cerebellopontine angle region. After discharge, he started experiencing reduced hearing in both ears (left > right) which gradually progressed over a period of 2–3 months into profound deafness. His pure tone audiometry and auditory brainstem response were suggestive of bilateral profound sensorineural hearing loss. MRI [Figure 1] and HRCT temporal bones [Figures 2 and 3] of the patient revealed a diagnosis of bilateral labyrinthitis ossificans.

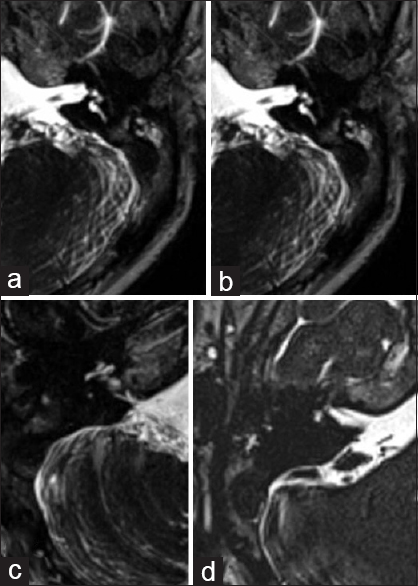

- Axial high-resolution thin T2 images of magnetic resonance imaging of left (a and b) and right inner ear (c and d) revealed normal signal intensity of cochlear turns (a) with the loss of normal hyperintense signal involving the vestibule and semicircular canals on the right side. (b) On left side, there was loss of normal cochlear signal (c) with only partial visualization of parts of lateral and superior semicircular canals (d)

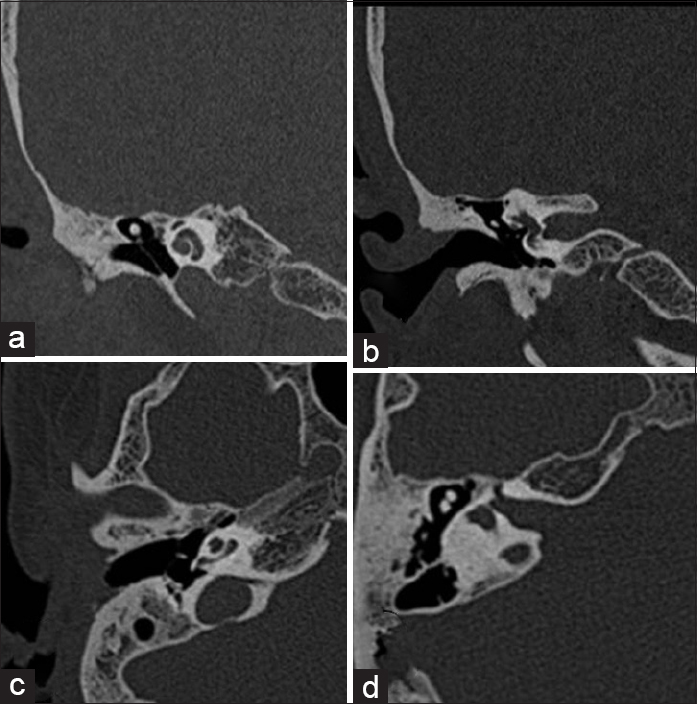

- Axial (a and b) and coronal (c and d) high-resolution computed tomography sections of right temporal bone showing the presence of normal cochlea (a and c), no calcification or ossification of superior and lateral semicircular canals (b) with ossification in posterior semicircular canal (d)

- Axial (a and b) and coronal (c and d) high-resolution computed tomography sections of left temporal bone showing complete ossification of the cochlea (a) with ossification of posterior semicircular canal (c) Left lateral and superior semicircular canals show no evidence of (b and d)

Bacterial meningitis is the most common cause of acquired sensorineural hearing loss in children seen in up to 5–7% of cases.[1] Window of the cochlea, window of vestibule, or both are shown to be route for infection dissemination to the inner ear. In case of bacterial meningitis, ossification is more extensive and route of entry to the inner ear is through subarachnoid space, cochlear aqueduct, and through inner acoustic meatus.[2]

Irrespective of the etiology, labyrinthitis ossificans pathogenesis involves an acute early stage where there is the presence of bacteria and leukocytes forming an inflammatory response in the perilymphatic spaces which is followed by proliferation of fibroblasts and finally.[3] formation of osteoid matrix.

HRCT is traditionally the imaging study of choice for preoperative assessment of cochlear implant. Drawbacks of HRCT include the inability to detect early fibrosis, partial volume averaging, and suboptimal assessment of the cochlear region compartments. MRI allows earlier diagnosis of labyrinthine ossificans as a result of its ability to demonstrate low T2 signal in the fibrous phase of labyrinthitis ossificans.[4]

In our patient, there was a loss of normal T2 hyperintensity seen in the right vestibule and semicircular canals which, however, did not show any ossification on computed tomography likely due to fibrotic phase of labyrinthitis ossificans. On the right side, there was ossification in the cochlea that also showed loss of normal signal on the T2-weighted image. There was a loss of normal signal intensity involving the superior and lateral canals appearing normal on HRCT which again likely represent fibrotic area. Thus, high-resolution T2 three-dimensional sequences provide higher sensitivity to detect the extent of disease as in our case.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pediatric sensorineural hearing loss, part 2: Syndromic and acquired causes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:399-406.

- [Google Scholar]

- Onset of hearing loss in children with bacterial meningitis. Pediatrics. 1984;73:575-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advantages of magnetic resonance imaging over computed tomography in preoperative evaluation of pediatric cochlear implant candidates. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:976-82.

- [Google Scholar]