Translate this page into:

Perception of service satisfaction and quality of life of patients living with schizophrenia in Lagos, Nigeria

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

To assess service-satisfaction and quality of life among patients with schizophrenia in a tertiary psychiatric healthcare facility in Lagos, Nigeria.

Methods:

Cross-sectional survey of 101 (out of 120) patients diagnosed with schizophrenia attending the outpatient clinic of the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis (SCID), Charleston Psychiatric Out-patient Scale (CPOSS), and the World-Health Organisation Quality of Life –Bref scale (WHOQOL-BREF) was used in assessing diagnosis, patient satisfaction and subjective quality of life respectively.

Results:

The ages of the patient ranged from 19-81. Males (49.5%) and females (50.5%) had almost equal distribution. Mean duration of attendance was 8.7years ± 8.50. Service satisfaction ranged between 25-60 on the CPOSS. Areas that had higher mean scores on CPOSS were with items (1) Helpfulness of the records clerk (3.70±1.1), (7) Helpfulness of services received (3.69±1.0). Subjective quality of life was high (3.65±1.8), satisfaction with health was also high (3.40±1.1). Service satisfaction correlated with Quality of life at P < 0.00.

Keywords

Perception

schizophrenia

service satisfaction

Introduction

Patient satisfaction and subjective quality of life (QOL) are important evaluations in assessing the quality of care from patient's perspective.[1234] The nature of both measures highlights the pivotal role given to patient's perspective of treatment and living conditions in shaping the goal of therapeutic interventions.[5] Measurements of satisfaction and QOL at its core aim to provide a comprehensive capture of the individual's level of satisfaction with medical care and subsequent adjustment in the context of the disorder.[4] These important subjective evaluative concepts generate useful information that can be helpful in planning and administering therapeutic interventions and rehabilitative programs by mental health professionals involved in the care of individuals with mental illnesses including schizophrenia. It also redirects the aim of treatment beyond relieve of symptoms to accommodate a totality of care.[67]

There is no all-encompassing definition of what actually constitutes patient satisfaction and QOL that exists in literature.[89] However, both share similarities in evaluating subjective cognitive evaluations that are affected by the emotional, social, and physical components associated with the experience of an illness and outcome of care.[89101112] Studies in Western lands had reported that self-perceived QOL is predictive of perception of satisfaction with health services.[13]

Schizophrenia exerts a heavy toll on the lives of individuals suffering from the disease. The chronic debilitating nature of the disorder makes it necessary for individuals with the disorder to have frequent contacts and follow-up visits with mental health care. The level of satisfaction with mental health care had been reported to influence compliance with treatment and has a positive effect on the lives of people with the disorder.[10] Efforts to improve service satisfaction and thus improve the QOL of these patients should be a worthwhile goal of mental health practitioners.

In Nigeria, as in other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, the living condition of patients with the disorder also face high level of stigmatization, heavy financial burden, poor socioeconomic environment, and paucity of mental healthcare service.[14151617]

Knowledge of the relationship between service satisfaction and QOL can help improve the quality of care delivery in the treatment and management of this particular group of patients in our environment. It will also add to the existing data from which hospital personnel and administrators can use to improve health care delivery and QOL to patients with schizophrenia.

The aim of the study was to examine the relationship between these two self-evaluative concepts among a unique group of patients who are often neglected in the audit process.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the outpatient clinic the Federal Neuro-Psychiatric Hospital Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria. It is the biggest federally funded stand-alone (specialist) psychiatric institution in Lagos, Nigeria. The clinic caters for the mental health needs of the population in the cosmopolitan city of Lagos. The clinic is well organized under the supervision of consultant psychiatrists. It runs from Monday to Friday except Wednesdays and functions between 8 am and 4 pm. Patients are usually given scheduled appointments on different clinic days.

Study design and procedure

The study was a cross-sectional survey of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia attending the outpatient clinic on all the clinic days. On every clinic day, patients were recruited from the consecutive attendees at the clinic. In all, one hundred twenty adult patients were recruited.

These patients were selected based on the following criteria: (1) Diagnosed with schizophrenia by a consultant psychiatrist, (2) had been attending the clinic for at least a year (to ensure acquaintance with most aspects of the clinic), and (3) were clinically stable to engage in the interview session. In addition, patients with severe cognitive deficits, affective disorders, and organic disorders were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from each participant in the study. Approval was given by the Hospital Ethics Committee.

Data collection

Research version of structured clinical interview Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV axis-I

The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (SCID) was used to establish the diagnosis of schizophrenia among the participants. The instrument is a diagnostic semistructured interview designed to increase the reliability of diagnosis by mental health professionals.[18] It assesses psychiatric disorders described in the fourth (IV) edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV Axis-I of the American Psychiatric Association. It was designed to increase the reliability of diagnosis by mental health professionals. The instrument has been reported to have good reliability in Nigeria.[19] The interviewers were trained in the use of the instruments by a certified trainer for over 2 weeks before the start of the study. The inter-rater reliability among the 2 interviewers was 0.8.

Sociodemographic questionnaire

Sociodemographic questionnaire was designed by the authors to capture the relevant sociodemographic and clinical data, such as age, sex, employment status, marital status, education, duration of attendance, and frequency of admission.

Charleston psychiatric outpatient satisfaction scale

This is a 15-item questionnaire scored on a five-point E5 response format with a score of “1,” poor; “2,” fair; “3,” good; “4,” very good; and “5,” excellent. The last item (15) is rated on a four-point scale (1 = Yes, Definitely; 2 = Yes, Probably; 3 = No, definitely; and 4 = No, Probably). It was developed at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, in the United States of America.[20] The instrument is made up of 15 items. The items on Charleston psychiatric outpatient satisfaction scale (CPOSS) were developed to cover administrative, clinical/treatment areas, and environmental areas. Some of the items on the scale were reworded for clarity and to be more akin with the nature of the service provided in the Hospital so item (1) helpfulness of the secretary was readjusted to read Helpfulness of the Records Clerks. Item 14 on clear and monthly bill was readjusted to read cost of medication and services. The overall satisfaction was calculated from the sum of the 13 items excluding the 2 anchor items. The scores are scaled in a positive direction with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction. The possible range of total scores of CPOSS was from 13 to 65.

The reliability and validity of the CPOSS has been reported in Nigeria by Ukpong et al.[21] They reported that the internal consistency was high (a = 0.91) and convergent validity was 0.30–0.68.

The interviews were conducted by the authors and trained senior resident doctors who had spent at least 3 years in the residency program.

World Health Organization quality of life-BREF

The World Health Organization QOL-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) was used in assessing the QOL of the participants.[22] WHOQOL-BREF is a short – version of WHOQOL-100. It measures the subjective QOL. It was developed in different sociocultural environments which makes it an international instrument applicable in most cultures for the measurement of subjective QOL. The WHOQOL-BREF is a 26-item questionnaire. Each of the 26 items is rated on a likert-type response from 1 to 5 with higher scores denoting a better QOL. It produces a profile in four domains of Domain 1 (Physical Health), Domain 2, (Psychological Health), Domain 3 (Social Relationship), and Domain 4 (Environment). QOL and satisfaction with health are items on the instrument that are scored and reported separately and are used to record to overall QOL and general health, respectively. Each domain consists of facets (sub-domain), which are made up of the remaining 24 items and calculated according to the instructions in the manual. The possible range of raw scores for physical domain is 7–35, psychological 6–30, social 3–15, and environment 8–40. The mean score of items within each domain was used to calculate the domain score.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science version 17 (SPSS Inc.,). Frequency distribution and mean scores and standard deviations were computed for sociodemographic variables for the variables. The means of patients' sociodemographic and clinical variables were compared with the overall satisfaction, QOL and health satisfaction scores using independent t-test for sex and one-way analysis of variance for clinical variables. QOL, satisfaction with health domains, and items on WHOQOL were correlated with overall satisfaction using Pearson's product moment correlation. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. Incomplete data were excluded using list-wise deletion.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical variables

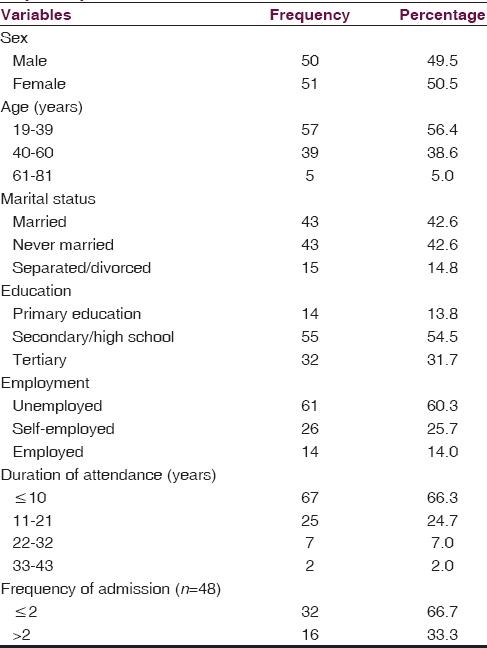

One-hundred twenty patients were recruited for the study. One-hundred one completed the interview process with the researchers (response rate of 84%). The sex distribution was fairly equal consisting of 50 males (49.5%) and 51 females (50.5%) [Table 1], the age range of the participants was from 19 to 91 years and mean age was 39.0 ± 1.2 years. There was equal number of married 43 (42.6%) and never married 43 (42.6%) participants [Table 1]. More than half had only secondary school education 55 (54.5%), and the number of unemployed was 51 (50.5%). A history of admission was reported by 48 (47.5%) of the participants [Table 1]. Most (66.3%) had been attending the clinic within the last 10 years, and mean was 8.70 ± 8.50 years [Table 1].

Service satisfaction using the Charleston psychiatric outpatient satisfaction scale

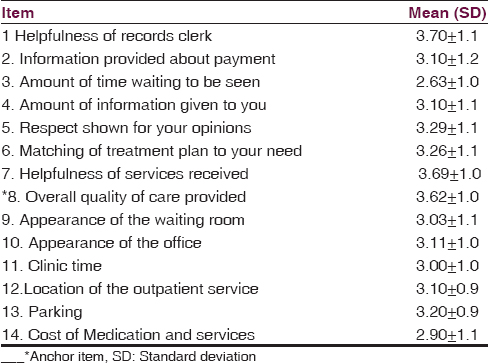

The satisfaction scores ([Σitem 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9–14]) on the CPOSS ranged from 25 to 60, with a mean of 40.17 ± 7.5. The modal score was 43.0 (66% of maximum possible score on CPOSS) as shown in Table 2.

Comparatively to scores on other items on the scale, lower mean scores were recorded on items (3) amount of time waiting to be seen (2.63 ± 1.0), items (14) cost of medication and services (2.90 ± 1.1). The highest mean scores were with items (1) helpfulness of the records staff, (3.70 ± 1.1), (15) willingness to recommend the service (3.76 ± 0.7), item (7) helpfulness of services received (3.69 ± 1.0).

The mean score on the anchor item 8 (perception of the overall quality of care provided) was 3.62 ± 1.0. On willingness to recommend the service (item 15), 92% of respondents were willing to recommend the service.

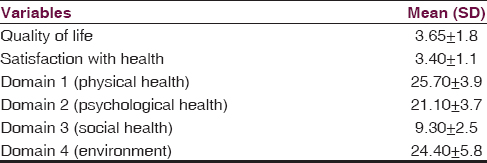

Quality of life and health satisfaction

The mean score for QOL on the WHOQOL-BREF was 3.65 ± 1.8, and mean score for satisfaction with health was 3.40 ± 1.1 (mode = 4) [Table 3]. Scores for the domains were Domain 1 (physical health), 25.70 ± 3.9; Domain 2 (psychological health), 21.10 ± 3.7; Domain 3 (social relationship), 9.30 ± 2.5; and Domain 4 (environmental), 24.40 ± 5.8 [Table 3].

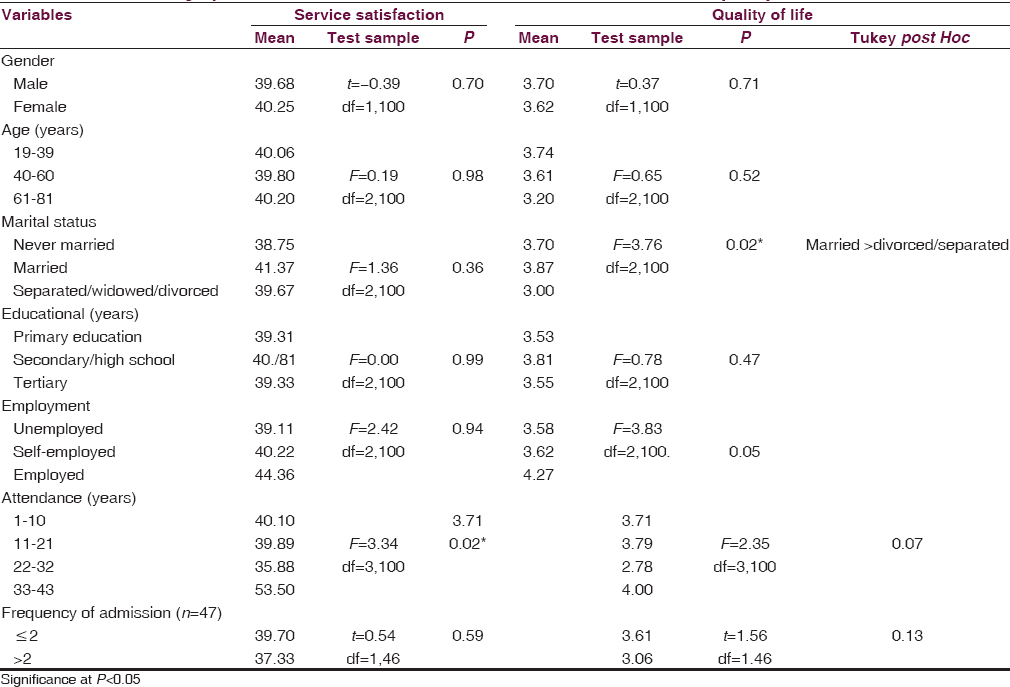

Sociodemographic/clinical variable factors associated with service satisfaction, quality of life, and health satisfaction

Duration of attendance at the clinic was the only sociodemographic factor associated with service satisfaction (P = 0.02) whereas marital status was the only sociodemographic factor that was significantly associated with QOL at (P = 0.02). Those who had spent 22–32 years at attendance were more likely to have higher mean score on the CPOSS than those within the 33–43 year category while those who were married significantly reported higher mean score on the QOL than those who were not married, divorced, or separated. Age, sex, educational status, employment statusand, number of admissions were not significantly associated with service satisfaction or QOL. Those who were married had higher mean rating on the higher mean score (F = 3.18, P = 0.02) as shown in Table 4.

Correlations of World Health Organization quality of life-BREF with Overall Service Satisfaction on Charleston psychiatric outpatient Satisfaction scale

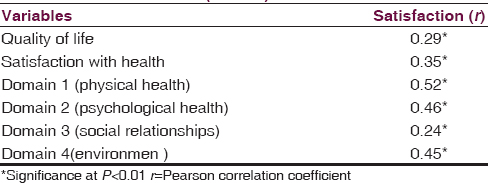

Subjective QOL was positively correlated with service satisfaction (r = 0.29 P = 0.00, n = 101). Service satisfaction was significantly correlated with the domains on the WHOQOL-BREF [Table 5].

Discussion

Our study examined the perception of service satisfaction and subjective QOL of patients with schizophrenia in a major psychiatric health facility in Lagos, Nigeria. We found a positive correlation between patient satisfaction and QOL of participants. It is noteworthy that the findings in our local centethr did not differ from results obtained from similar studies done in more developed Western countries.[13] The commonality of these results among these groups of patients seems to suggest that perception of service satisfaction is strongly related to perception of QOL.

The moderately high mean scores obtained on the CPOSS reveal a level of appreciation of the service delivery at the hospital by the participants despite the limitations inherent within the health facility. High levels with services were in areas that appraised one-on-one interaction with mental health professionals and personnel. There areas include helpfulness of the records clerk (3.70), helpfulness of services received (3.69), and the anchor item-overall quality of care (3.62). These areas highlight the premium level of satisfaction placed on these interactions as much more satisfactory than matching treatment plans to their needs (3.26). It shows the importance of valuing attitudes we show to patients, and on personal interactions with them.

Prior studies in developed lands had also reported that psychiatric patients (inclusive of patients with schizophrenia) place more importance on attitude of staff in evaluating their perception of healthcare service.[23] This is quite interesting that despite the dearth of facilities and personnel involved in mental health service in our setting in comparison to Western countries, similar views had been expressed. For example, in a study done in United States of America (USA), using the CPOSS, areas such as helpfulness of the clerk/records, clerk/overall quality of care helpfulness of services received also had higher mean ratings.[20]

High levels of satisfaction with psychiatric services have also been reported in previous satisfaction studies in both in- and out-patient services in Nigeria.[2124] Mean scores obtained from this study were similar to the findings of a study done among psychiatric patients from diverse diagnostic groups in a semi-urban setting in Nigeria, although the range of mean scores was lower in our own study. The differences may be due to the setting; however, the general findings had much lower mean in all items of measure in comparison to the findings of a survey of patients attending a psychiatric outpatient clinic in the United States of America.[2021]

Also, unlike previous studies of satisfaction, our own survey was limited to patients with schizophrenia and their perception of service satisfaction may be different from other patients living with other psychiatric disorders.[25]

Low areas of satisfaction were recorded on items assessing cost of billing and waiting time. The low economic status of many of these patients creates difficulty for most patients in footing the cost of services.[26] Low satisfaction with waiting time is equally observed at most government out-patient clinics in underdeveloped countries due to poor funding and organization of healthcare service and high patient–doctor ratio and had also been reported even among general outpatients.[27] Waiting times and cost of services is a major constraint to quality service delivery in Nigeria and sub-Sahara Africa in general.[27] We observed that the amount of information given to you and information about payment had relatively same lower mean scores (3.10), respectively, in comparison to helpfulness of services (3.69), and helpfulness of the records clerk (3.70). To our participants, their perception of information dissemination within the hospital is not as satisfactory as some other aspects of care. It shows a need to improve the information dissemination within the hospital. In contrast, participants from a prior study reported a high level of satisfaction with the waiting time. This may be as a result of the highly organized healthcare settings and number of personnel in facilities characteristics of healthcare services in Western lands.

It is interesting that sociodemographic factors such as age, sex, and employment status were not significantly associated with satisfaction. The perception of satisfaction by our participants did not significantly differ across these variables, and participant's sociodemographics were rarely a factor in appreciation of services. Also, there has been no consistently reported association of sociodemographic pattern with satisfaction even from studies in other countries.[11328]

High ratings of QOL and satisfaction with health by patients with schizophrenia despite living in objectively poor environment have been an often reported findings in Nigeria and in various other societies.[2930] The reason for this is unclear, but as some authors have suggested, it may be due to a number of interplaying forces such as the minimization of the effect of the disease on their life, poor insight, lowered expectation, and different approaches and construct when assessing living conditions subjectively and objectively.[2931] The sociocultural orientation in most parts of the southwest Nigeria in being positive about one's situation may also be a contributory factor to high ratings of QOL rating among participants. As reported by some authors in a survey of QOL of patients with schizophrenia across several European communities, the QOL appears to be associated with local style of living and culture.[32]

Comparatively, social domain had the lowest recorded scores on the WHOQOL-BREF scale. Expectedly, these areas may indicate the difficulties participants in adjusting to social relationships. This may be due to the chronic and debilitating nature of the disorder and social distancing which affects patient ability to seek meaningful relationships.[33]

Our study shows a positive correlation between domains the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire with perception of service satisfaction. The positive correlation with patient satisfaction seems to support studies that report that patients who are generally satisfied with their health service delivery, also feel similarly about most areas of their health and their QOL.[28] Prioritizing patient satisfaction in service delivery to these groups of patients can have a positive relation with their perception of QOL and vice versa.

The limitation in this study is the cross-sectional study design, which limits the generalization of the results. Although efforts were made to assess the insight by the clinicians, the reliance on their self-report can be doubtful. There was no comparison among different diagnostic groups. In addition, subjective assessments of patient reports can be influenced by different situational factors and may not always be reliable. We also do know that participants may also refrain from giving responses that are critical of personnel and the institution to curry future favors.[34]

Conclusion

The study focused on the relationship between service satisfaction and QOL among patients with schizophrenia. Participants' perception of service satisfaction was positively correlated with perception of their QOL. The study showed that participants had high mean rating of satisfaction on attitudes shown by mental health staff toward them. Satisfaction was highest with the helpfulness of the records clerk, helpfulness of services received and overall quality of care participants reported a high subjective rating of their QOL. The study also revealed areas that are significant to both QOL and service satisfaction which should be given attention by mental health practitioners in planning and managing outpatient services that will satisfy the needs of patients and aid holistic treatment. In future, there will be need for multicenter studies for comparison among different settings. There will also be need to make these surveys a mandatory assessment as part of evaluation of the quality of care of mental health service delivery.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would wish to thank Dr. Caleb-Gbiri for the invaluable advice in preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Patients' and relatives' satisfaction with psychiatric services: The state of the art of its measurement. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994;29:212-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient satisfaction: A valid index of quality of care in a psychiatric service. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:330-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient satisfaction with anaesthesia care: What is patient satisfaction, how should it be measured, and what is the evidence for assuring high patient satisfaction? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2006;20:331-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Managing performance and performance management: Information strategy and service user involvement. J Manag Med. 2002;16:78-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- The quality of life of patients suffering from schizophrenia – A comparison with healthy controls. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2011;155:173-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subjective and objective dimensions of quality of life in psychiatric patients: A factor analytical approach: The South Verona Outcome Project 4. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:268-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progress report to Thomas Linacre. Reflections on medicine and humanism. Linacre Lecture 1963. Univ Q. 1963;17:327-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Concepts of quality of life in mental health care. In: Priebe S, Oliiver JPJ, Kaiser W, eds. Quality of Life and Mental Health Care. Philadephia: Wighston Biomedical; 1999. p. :19-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life issues in mental health care: Past, present and future. Ger J Psychiatr. 2004;7:35-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient satisfaction: A review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1829-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health-related quality of life in the evaluation of medical therapy for chronic illness. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:377-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multivariate analysis of outcome of mental health care using graphical chain models. The South-Verona Outcome Project 1. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1421-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of noncompliance in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1121-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life measurement in mental health. Introduction and overview of workshop findings. Can J Commun Ment Health. 1998;3:9-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subjective quality of life of recently discharged Nigerian psychiatric patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:707-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation and Ministry of Health Nigeria – World Health Reports – AIMS Report on Mental Health System in Nigeria 2006

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV ® Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version, Administration Booklet. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub.; 2012.

- Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:465-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- A brief scale for assessing patients' satisfaction with care in outpatient psychiatric services. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:816-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reliability and validity of a satisfaction scale in a Nigerian psychiatric out-patient clinic. Niger J Psychiatr. 2008;6:31-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:1569-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Client satisfaction, extended intervention and interpersonal skills in community mental health. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18:246-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient and staff satisfaction with the quality of in-patient psychiatric care in a Nigerian general hospital. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:283-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient satisfaction with quality of primary health care in Benghazi, Libya. 2010. Libyan J Med. 5:1-7. doi:10.3402/ljm.v5i0.4873. Available from: http://doi.org/103402/ljm.v5i0.4873

- [Google Scholar]

- Financial cost of treating out-patients with schizophrenia in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:364-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Patient satisfaction with the services provided at a general outpatients' clinic, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2005;34:133-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Satisfaction with mental health services among people with schizophrenia in five European sites: Results from the EPSILON Study. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:229-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subjective life satisfaction and objective living conditions of patients with schizophrenia in Nigeria. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:314-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia in Nigeria. Niger Med Pract. 2005;48:36-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intervention research in psychosis: Issues related to the assessment of quality of life. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:557-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia in five European countries: The EPSILON study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:283-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social distance towards people with mental illness in Southwestern Nigeria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:389-95.

- [Google Scholar]