Translate this page into:

Validation of the Tamil version of short form Geriatric Depression Scale-15

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Local language screening instruments can be helpful in early assessment of depression in the elderly in the community and primary care population. This study describes the validation of a Tamil version of Geriatric Depression Scale (short form 15 [GDS-15] item) in a rural population.

Materials and Methods:

A Tamil version of GDS-15 was developed using standardized procedures. The questionnaire was applied in a sample of elderly (aged 60 years and above) from a village in South India. All the participants were also assessed for depression by a clinical interview by a psychiatrist.

Results:

A total of 242 participants were enrolled, 64.9% of them being females. The mean score on GDS-15 was 7.4 (±3.4), while the point prevalence of depression was 6.2% by clinical interview. The area under the receiver-operator curve was 0.659. The optimal cut-off for the GDS in this sample was found at 7/8 with sensitivity and specificity being 80% and 47.6%, respectively.

Conclusion:

The Tamil version of GDS-15 can be a useful screening instrument for assessment of depression in the elderly population.

Keywords

Depression

geriatric

Geriatric Depression Scale-15

India

validation

Introduction

Depression affects a significant proportion of the geriatric population.[1] It is associated with poorer quality-of-life, higher mortality rates, and is often unrecognized.[234] Depressive symptoms in the elderly are often considered a natural process of ageing and are likely to be missed by clinicians.[5] Prompt recognition of depression in the geriatric age group can help in earlier treatment and can improve the outcomes of sufferers.[6]

Since the elderly are unlikely to directly seek help for their depressive symptoms, screening instruments can be utilized to assess depression in the primary care population and the community. Geriatric Depression Scale-short form (GDS-15) is a brief 15-item instrument validated as a screening tool for depression based on self-reported feelings over the past 1-week.[7] “Yes” response to negatively worded questions and “No” response to positively worded questions are given a score of one. A total score of 5 or more suggests the presence of depression. The scale has been utilized in the clinical as well as research setting.

Wider and cross-cultural use of GDS requires translation and validation of the instrument in different languages. The GDS has been translated in many languages including Arabic and Japanese.[89] Tamil is an Indian language which is also spoken in Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Singapore. Since more than 60 million of the world population speaks Tamil,[10] a Tamil version of the scale is required. A Tamil version of the GDS-15 may be helpful for nonmultilingual subjects, and likely to take care of culturally sensitive issues. Hence, the present article describes the translation and validation of the Tamil version of GDS-15.

Materials and Methods

Initial translation and back-translation

Briefly, GDS is a self-rated depression screening instrument that has 15 items which are rated in yes/no format. The original 15-item English version of the GDS scale was translated to Tamil by two bilingual literary experts independently who had no knowledge about the scale (its content, purpose and interpretation). They made one single Tamil translated version by mutual consensus on the use of appropriate words. The Tamil version of the scale was then pilot tested in a small sample of elderly subjects (n = 10) recruited from the hospital setting to assess for difficulties in understanding of the questions. Finer modifications were made in the scale in accordance with the suggestions received during the pilot testing phase. Data during piloting were collected by two persons, one was a social worker and another was a clinical psychologist. Based on their feedback appropriate changes in the colloquial terms were made in the Tamil version. Then a bilingual psychiatrist not involved in the project was asked to give feedback over the scale related to its ease of administration and ease of understanding without losing its meaning, and changes suggested by him were made in the Tamil version. The Tamil version was then back-translated by two bilingual medical professionals to assess for similarity with the English version of the scale, which was verified by the same bilingual psychiatrist. The back translation of the scale concurred with the original version and the translation was deemed adequate. The final translated version of the scale is in Appendix 1.

Application in a larger sample

The scale was then applied in a larger community sample of the elderly population. The Tamil version of the scale was applied to all available elderly individuals (aged 60 and above) in a village in Puducherry. A single village population was considered adequate to ascertain validity characteristics of the scale. The village had a sizable and stable elderly population.

The assessment of the elderly was conducted through house-to-house survey by research workers. If the individual was not available on the three attempts over a period of 4 weeks, then the subject was considered as drop-out from the study. Informed consent was sought from the individuals and their legally acceptable representatives for inclusion in the study. Information relating to demographic characteristics, medical illnesses, and cognitive functions was ascertained. Thereafter, the Tamil version of the scale was applied. The questions were read out to individuals who were illiterate or had a visual impairment which precluded reading. Cognitive scores were not used to determine eligibility, but those with significant impairment that precluded an interview were excluded.

Concurrent validity with psychiatric interview

The elderly individuals were then assessed by a qualified psychiatrist for confirmation of the presence of depression. This assessment was conducted within a week of the assessment using Tamil version of GDS. The psychiatrist was unaware of the screening result at the time of assessment, and independently made a clinical diagnosis of depression using unstructured interview conducted in Tamil as per International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10).[11] Subsequently, the different cut-offs of the GDS scale were evaluated with clinician-rated ICD-10 diagnosis as the gold standard. The receiver-operator curve was plotted with to graphically depict the incremental sensitivity and specificity. Youden's statistic was used to determine the optimal cut-off for sensitivity and specificity.[12] Youden's J is calculated as: Sensitivity + specificity − 1.

Results

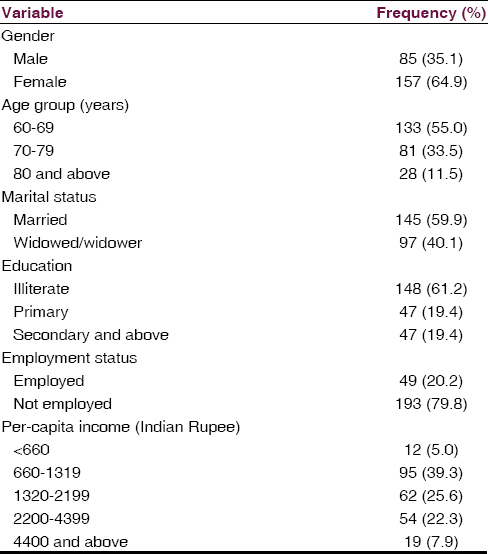

The sample comprised of 242 participants of the village. The characteristics of the sample are depicted in Table 1. A majority of the sample comprised of females (64.9%), was aged 60–69 (55.0%), and was married (59.9%), illiterate (61.2%), and currently not employed (79.8%). The mean modified mini mental status examination score was 22.8 (standard deviation [SD] of 4.3). Major impairment with respect to at least one organ system was present in 86.8% of the sample.

The scores on GDS varied from 0 to 15 with a mean of 7.4 and an SD of 3.4. The median GDS score of the sample was 8, and the inter-quartile range was 5–10. The mean (SD) of GDS scores was 7.0 (3.3) and 7.4 (3.6) for males and females, respectively, with nonsignificant differences between the groups (Student's t = 1.358, P = 0.176). As per clinician diagnosis, 15 individuals could be diagnosed as having depression as per ICD-10. This gave a point prevalence rate of depression as 6.2% in the sample. The prevalence of clinician diagnosed depression was 4.7% in males (4/85) and 7.5% among the females (11/157), the difference being nonsignificant (χ2 = 0.502, P = 0.584).

The ROC of the sample is shown in Figure 1. The area under the curve was 0.659 (95% confidence intervals of 0.516–0.803). The sensitivity, specificity, and Youden's statistic are shown in Table 2. The optimal cut-off for the GDS in this sample was found at 7/8 (i.e., score of 8 and above classifying for depression). The sensitivity of this score was 80% though specificity was somewhat lower at 47.6% for this cut-off. With this cut-off, no significant difference emerged between males and females (47.1% vs. 58.0%, χ2 = 2.640, P = 0.104).

- Receiver-operator curve

Discussion

The present study puts forth the results from Tamil translation and validation of GDS. Validation of GDS from across the globe has seemingly been helpful in advancing research in geriatric depression.[81314] The present scale similarly presents the characteristics of a validated scale for screening depression, for future usage in cross-sectional and longitudinal research.

The cut-off of the scale, where optimum fitting of sensitivity and specificity was found, was somewhat higher than the cut-off proposed by the English language validation of the scale.[715] Some of the other translations have also found similar cut-off as the English language validation.[16] However, certain other translations have found higher GDS cut-offs as in the present study.[91314] The specificity at the present cut-off score was found to be fairly low, suggesting false positives were picked up easily using the GDS.

Our findings go contrary to the majority of the studies that validates GDS-15 in different cultures and reported good to the excellent psychometric property. Some possible reasons for the lower area under the curve could be: in our population, majority of the elderly were illiterate, and the statements were read out to them, besides biases from interviewer or respondents, it could be inherent property of the scale to perform differently in different setting.[17] Scale scores tend to be influenced by age, chronic illness and ethnicity apart from gender.[18] Though we did not find the influence of gender on the scores, we did not exclude those with cognitive impairment or with chronic illness. These need to be explored. This being a screening instrument relies more on minimizing the false negatives. Some of the items of GDS were likely to be endorsed easily by the elderly rural population.

The findings of the study should be considered in the context of strengths and limitations. The study is the first to validate the Tamil version of GDS in a community sample. The translation and validation were done using standard techniques. The sensitivity and specificity for each of the cut-offs scores were determined. The limitations include lack of assessment of test-retest reliability. Concurrent validity of the English and Tamil version of the scale could not be done due to lack of bilingual elderly subjects in the elderly population from the catchment area. Interviewer bias could not be totally eliminated due to a considerable proportion of the participants being illiterate, and hence required assistance in completing the Tamil version of the questionnaire.

The present scale presents a valid and easy to administer Tamil version of GDS. The scale is likely to be helpful for clinicians across many countries for screening out depression in elderly Tamil patients. With gradual expanding research in the field of geriatric psychiatry in the region, the scale is expected to benefit investigators while assessing depression in Tamil speaking elderly population.

Source of Support: The present work was funded in part by grant from Indian Council for Medical Research.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:307-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of depression and gender with mortality in old age. Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL) Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:336-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minor and major depression and the risk of death in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:889-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depression and excess mortality: Evidence for a dose response relation in community living elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:169-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional analysis of factors that influence the detection of depression in older primary care patients. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:262-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. New York: The Haworth Press; 1986. p. :165-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factor structures of a Japanese version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its correlation with the quality of life and functional ability. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215:460-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Arabic version of the short Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:571-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Summary by Language Size. Ethnologue. Available from: http://www.ethnologue.com/statistics/size

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD.10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GDS-15 in Iranian elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:588-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- The validation of the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece. Aging (Milano). 1999;11:367-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:376-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity of the Brazilian version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) among primary care patients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:109-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Use of GDS-15 in Detecting MDD: A Comparison Between Residents in a Thai Long-Term Care Home and Geriatric Outpatients. J Clin Med Res. 2013;5:101-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differential item functioning of the Geriatric Depression Scale in an Asian population. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:285-90.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix 1: Geriatric Depression Scale-15 Tamil version