Translate this page into:

Histological-subtypes and anatomical location correlated in meningeal brain tumors (meningiomas)

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Not enough literature is available to suggest a link between the histological subtypes of intracranial meningeal brain tumors, called ‘meningiomas’ and their location of origin.

Aim:

The evidence of correlation between the anatomical location of the intracranial meningiomas and the histopathological grades will facilitate specific diagnosis and accurate treatment.

Materials and Methods:

The retrospective study was conducted in a single high-patient-inflow Neurosurgical Center, under a standard and uniform medical protocol, over a period of 30 years from December 1982 to December 2012. The records of all the operated 729 meningiomas were analyzed from the patient files in the Medical Records Department. The biodata, x-rays, angiography, computed tomography (CT) scans, imaging, histopathological reports, and mortality were evaluated and results drawn.

Results:

The uncommon histopathological types of meningiomas (16.88%) had common locations of origin in the sphenoid ridge, posterior parafalcine, jugular foramen, peritorcular and intraventricular regions, cerebellopontine angle, and tentorial and petroclival areas. The histopathological World Health Organization (WHO) Grade I (Benign Type) meningiomas were noted in 89.30%, WHO Grade II (Atypical Type) in 5.90%, and WHO Grade III (Malignant Type) in 4.80% of all meningiomas. Meningiomas of 64.60% were found in females, 47.32% were in the age group of 41-50 years, and 3.43% meningiomas were found in children. An overall mortality of 6.04% was noted. WHO Grade III (malignant meningiomas) carried a high mortality (25.71%) and the most common sites of meningiomas with high mortality were: The cerebellopontine angles, intraventricular region, sphenoid ridge, tuberculum sellae, and the posterior parafalcine areas.

Conclusion:

The correlation between the histological subtypes and the anatomical location of intracranial meningeal brain tumors, called meningiomas, is evident, but further research is required to establish the link.

Keywords

Anatomical origin

correlation

histological types

intracranial meningiomas

Introduction

Meningeal brain tumors, called meningiomas, are now known to arise from arachnoidal cap cells of the leptomeninges. In 1915, Harvey Cushing considered that meningeal tumors arose from arachnoidal cap cells. Seven years later, Cushing proposed the term ‘meningioma’ for these tumors and the term achieved global acceptance. Working together with his student, Percival Bailey, at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, he adopted a histopathological classification system that listed four variants: Meningothelial, fibroblastic, angioblastic, and osteoblastic. Later, Bailey and Bucy expanded the initial histopathological classification of meningiomas, which was similar to the new WHO histopathological classification 2007, despite new discoveries made by molecular biology, biochemistry, and a recent technology in the last few years.[1]

Intracranial meningiomas are always dural-based, but entities like intraventricular meningiomas arise independent of such a base. Similarly, histopathological atypicality occurs among meningiomas of the posterior fossa, base of the skull, intraventricular, and parasagittal/falcine regions. As the WHO grading has categorized meningiomas in benign, atypical, and malignant types, the curiosity to know the probable histological type preoperatively, by the site of origin, may change the future management of meningiomas, in the form of extension of resection and adjuvant treatment.

Materials and Methods

The authors sought to analyze all the admitted 729 surgically treated meningiomas (meningeal tumors of the brain) and those treated under a standard medical protocol in a high-patient-inflow and the only Neurosurgical Unit in the State, from December 1982 to December 2012. Ethnically, all the patients belonged to the same area. Retrospectively, the biodata, surgical procedure, histopathological findings, mortality, and imaging reports (in the form of initial X-rays, two-fourth vessel angiography, CT Scans, and recent MRI) of all the patients were recorded from the patient files in the Medical Records Department. The histopathological findings and types were categorized according to the WHO 2000 Classification of Meningiomas.[2]

The histological patterns recognized by the WHO are:

WHO grade I

-

Meningothelial (syncytial) meningioma

-

Transitional (mixed) meningioma

-

Fibroblastic (fibrous) meningioma

-

Psammomatous meningioma

-

Angiomatous (vascular) meningioma

-

Microcystic meningioma

-

Secretory meningioma

-

Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma

-

Metaplastic meningioma

WHO grade II

-

Chordoid meningioma

-

Clear-cell meningioma (intracranial)

-

Atypical meningioma

WHO grade III

-

Papillary meningioma

-

Rhabdoid meningioma

-

Anaplastic (malignant) meningioma

After compiling the whole data, observations were made, inferences drawn, and statistically, the Law of Variance used wherever applicable.

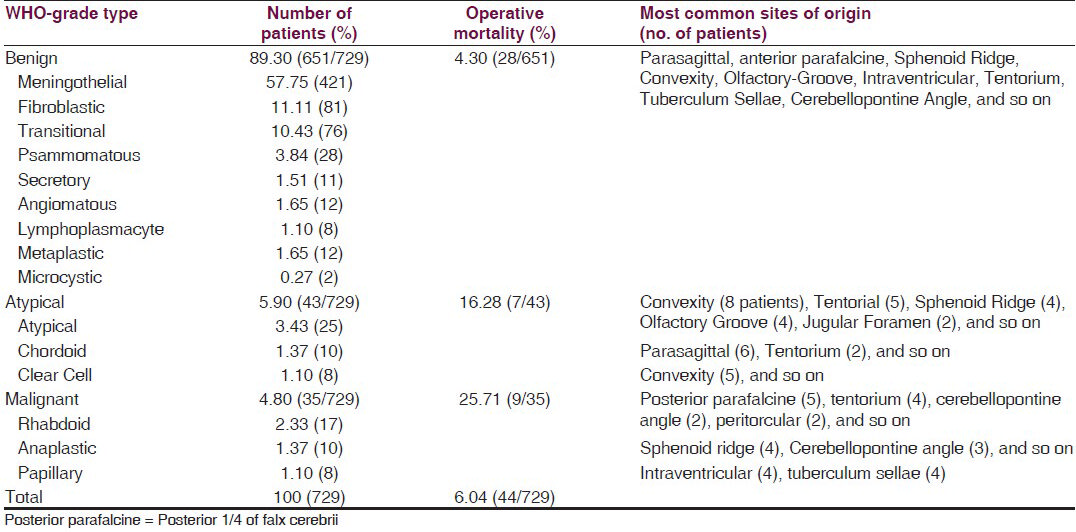

Observations

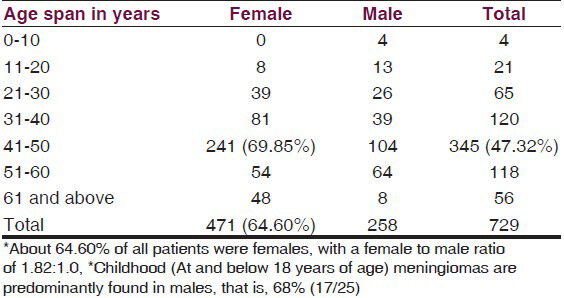

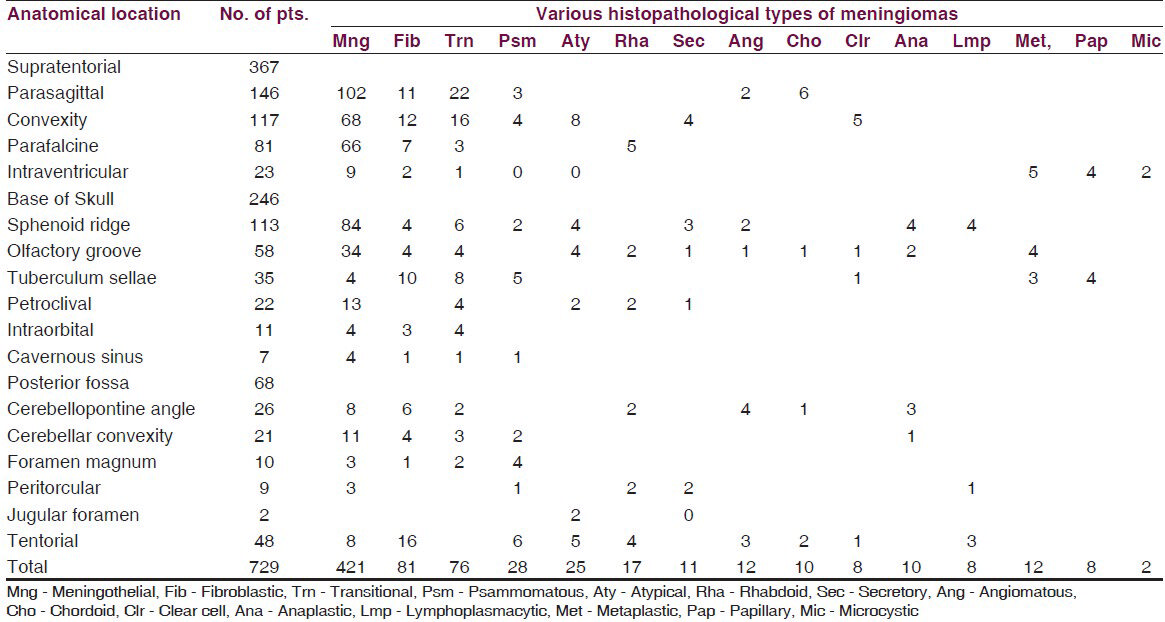

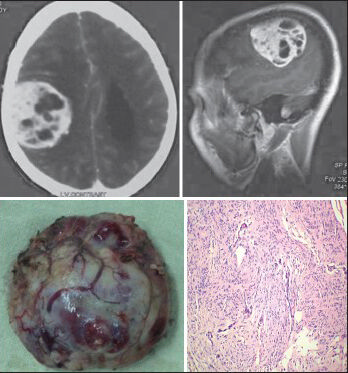

The analysis [Table 1] showed that of the 729 meningiomas patients, about 64.60% (471/729) were females. About 47.32% (345/729) of all patients were in the age group of 41–50 years, and of these 69.85% (241/345) were females. Childhood meningiomas (at and below 18 years of age) accounted for 3.43% (25/729) and were predominantly (68% =17/25) found in male children. There were only 0.55% (4/729) children (all males) below 10 years of age (youngest being eight years old) and 7.68% (56/729) elderly patients. They were mostly females (85.71% = 48/56) above 60 years of age (oldest being 72 years). The site of origin of half the meningioma cases (50.34% = 367/729) was the supratentorial compartment, whereas, 33.74% (246/729) originated from the base of the skull and the rest from the posterior fossa [Table 2]. The most common anatomical site of origin was the parasagittal area, that is, 20.02% (146/729), followed by 16.04% (117/729) from the cerebral convexity [Figure 1], 15.50% (113/729) from the sphenoid ridge; 11.11% (81/729) from the anterior and posterior parafalcine areas, and 7.95% (58/729) arose from the olfactory groove. Histopathologically, the common types of meningiomas, such as, the meningothelial (57.75% = 421/729), fibroblastic (11.11% = 81/729), transitional (10.43% = 76/729), and psammomatous (3.84% = 28/729), occurred in 83.12% (606/729) of the patients, whereas, the uncommon types of meningiomas, such as, atypical, rhabdoid, secretory, angiomatous [Figure 2], chordoid, clear cell, anaplastic, and so on comprised of 16.87% (123/729) of all meningiomas.

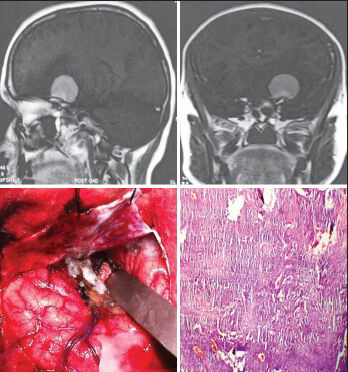

- The CECT scan and sagittal CEMRI of a 70-year-old male patient shows right frontoparietal convexity transitional (Benign) meningioma, with a biopsy specimen and a histopathological slide (H and E; original magnification ×100)

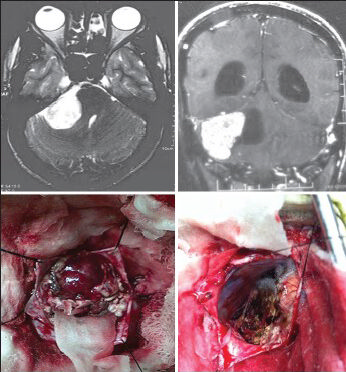

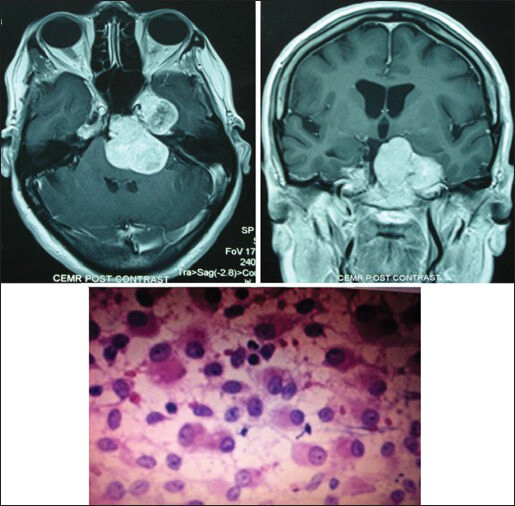

- The axial and coronal CEMRI and intraoperative photographs of a 65-year-old woman reveal angiomatous (WHO Grade I) cerebellopontine angle meningioma

Correlation between location and type

The most common histological type of meningioma was meningothelial (syncytial) and 24.22% (102/421) of these arose from the parasagittal region; 19.95% (84/421) from the sphenoid ridge [Figure 3]; 16.15% (68/421) from the cerebral convexity; 15.67% (66/421) from the anterior parafalcine, and 8.07% (34/421) arose from the olfactory groove areas [Table 2]. Similarly, the other common histological types, such as, the fibroblastic, transitional, and psammomatous, originated from the most common sites of origin such as, the parasagittal, anterior parafalcine, sphenoid ridge convexity, and tentorial regions. The WHO Grade I (Benign) meningiomas comprised of 89.30% (651/729) patients and included, among common variants, secretory [Figure 4], angiomatous, lymphoplasmacytic, metaplastic, and microcytic [Table 3]. The less common WHO Grade II (Atypical) meningiomas accounted for 5.90% (43/729) patients with 3.43% (25/729) atypical type [Figure 3] arising from the convexity, tentorium, and sphenoid ridge; 1.37% (10/729) chordoid type, based on the parasagittal and tentorial areas; and 1.10% (eight) clear cell-type, attached to the convexity. The rare malignant meningiomas or WHO Grade III were found in 4.80% (35/729) of all cases. The rhabdoid [Figure 5] variant of the malignant grade occurred in 2.33% (17/729) of all meningioma patients and its origin was found in the posterior parafalcine, tentorial, cerebellopontine angle, peritorcular [Figure 4], and other regions. The anaplastic type of WHO Grade III (malignant meningiomas) was diagnosed in 1.37% (10/729) of patients and arose mostly from the sphenoid ridge and cerebellopontine angles [Figure 2], whereas, the papillary variant of malignant meningiomas appeared in 1.10% (8/729) of all meningiomas and originated from the intraventricular and tuberculum sellae areas [Table 3]. An overall operative mortality of 6.04% (44/729) was noted for all patients, which appeared as high as 25.71% (9/35) in WHO Grade III (Malignant) variant and 16.28% (7/43) for the WHO Grade II (Atypical) type. However, the operative mortality of the WHO Grade I (Benign) variety was only 4.30% (28/651). High mortality was revealed for meningiomas originating from the cerebellopontine angle, sphenoid ridge, and the tentorial, intraventricular, tubercular sellae, and posterior parafalcine regions.

- The left sphenoid wing meningioma, on CEMRI, is seen in the intraoperative photograph; the histological slide shows atypical (WHO Grade II) meningioma (H and E; original magnification ×100)

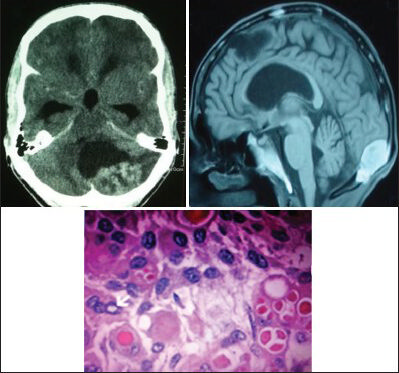

- Contrast CT scan and MRI of a 46-year-old male show peritorcular meningioma, which proved to be a secretory (Benign) meningioma (WHO Grade I) on histopathology (H and E; original magnification ×400)

- A petroclival meningioma on MRI and malignant features on histopathology proved Rhabdoid (WHO Grade III) meningioma (H and E; original magnification ×400)

Discussion

The lesion, most comparable with a meningioma, was first reported by Felix Plater in 1614.[3] A French surgeon, Antoine Louis in 1774, described a tumor-like meningioma and called it ‘fungus durae matris’.[4] However, Harvey Cushing was the first to use the term ‘meningioma’ in 1922.[3] The present study on 729 patients noted a female to male ratio of 1.82:1.0, the most involved being in the 41-50 year age group, and 3.43% childhood meningiomas. Benign (Grade I) meningiomas occurred in 89.30%, and 57.75% of all meningiomas were of the meningothelial (syncytial) type and the most common site of origin for these was the parasagittal area. The malignant (Grade II) variety occurred in 4.80% of the patients with common sites of origin in the cerebellopontine angles, intraventricular region, sphenoid ridge, and posterior parafalcine areas. A report of female preponderance was documented by Marin et al., with a female to male ratio of 2.5:1.[5] Gabriela et al. reported 100% cerebellar convexity meningiomas histologically as being fibrous alone, although most of the angiomatous subtypes originated from the cerebellopontine angles. The petroclival meningiomas accounted for a higher incidence of 11.42% for all posterior fossa meningiomas.[6] Park et al. reported that the vast majority of intracranial meningiomas (92%) had a benign histology, whereas, 8% showed atypical or malignant features. For all meningiomas, the most common histopathological subtype was the meningotheliomatous type (63%), followed by transitional (19%), fibrous (13%), and psammomatous (2%) meningiomas. Also, fewer than 10% of the meningiomas were malignant.[7] Gabriela et al. mentioned that grade I meningiomas were encountered in a majority of cases (82.85%), whereas, grade II meningiomas were diagnosed in 11.42% of the operated cases. The anaplastic meningiomas (grade III) accounted only for 5.71%. About 82% (29 patients) of the patients had an anatomically distinct attachment to the dura. The most common benign histological subtypes among the posterior fossa meningiomas were the fibrous (37.79%) and psammomatous (24.13%).[6] Marin et al. reviewed 492 intracranial and spinal meningiomas, among which, seven patients were identified to have foramen magnum meningiomas. These were five women and two men aged 39-66 years (mean 53.3 years). They found a female preponderance with a female to male ratio of 2.5:1.[5] Various studies show that foramen magnum meningiomas are rare and account for only 0.3 to 3.2% of all meningiomas, and between 4.2 and 20% of all posterior fossa meningiomas.[8910] The authors from the two studies reported that cerebellar convexity meningiomas represent about 1.5% of all meningiomas.[1011] Avninder et al. presented a case of a lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma arising at the foramen magnum.[12] Mahx Bracho et al. reported a three-year-six-month-old boy with chordoid meningioma of the foramen magnum.[13] On account of the rarity of the published cases, there is only limited information about the histology of these meningiomas. Tsao et al. presented the histopathology of a foramen magnum meningioma as a meningothelial type.[14] The present study, analyzing 729 meningiomas, in a age group of 8-72 years, revealed [Table 3] different sites of origin for WHO Grade I (Benign = 89.30%), II (Atypical = 5.90%), and III (4.80%) histopathological variants. The Benign (I) and Atypical (II) mostly had their origin in the parasagittal, anterior parafalcine, convexity, sphenoid ridge, and olfactory groove areas. However, among the Malignant (III) meningiomas, subtype rhabdoid (2.33%) originated mostly from the posterior parafalcine, tentorial, cerebellopontine angle, and peritorcular areas. The subtype anaplastic (1.37%) arose from the sphenoid ridge and cerebellopontine angle regions. The papillary meningiomas (1.10%) were based in the intraventricular and tuberculum sellae regions. This indicates that the posterior fossa, skull base, and intraventricular regions are the seat for malignant meningiomas and also carry a high mortality. These observations appear comparable to the presently available literature. The reason why a meningioma at a specific site shows an altogether different histology depends probably on the cell of origin and milieu of the original site of meningioma. Wu et al. hypothesized that the angiomatous subtypes can only be found in the cerebellopontine angle, as the posterior petrous surface of the temporal bone is relatively unique in its relationship to the venous sinuses, because the sigmoid, superior petrosal, inferior petrosal, and cavernous sinuses form a ring surrounding the posterior face of the petrous bone and the meningiomas located in this region have a very close relationship with the four aforementioned sinuses.[15] Drevelegas et al. considered the location frequency of meningiomas and conceived that true meningiomas tend to occur where meningothelial cells and arachnoid cap cells are most numerous. The arachnoid granulations or villi have a large number of cap cells, and therefore, are common sites of origin for meningiomas, especially along the dural venous sinuses, where the villi are mostly concentrated, or along the cranial sutures where arachnoid granulations or the rest of the arachnoid cells are often present.[16] However, Lee et al. took into account the histology of the normal leptomeninges and explained the existence of many subtypes of meningiomas. The outer layer of the arachnoid membrane was formed by the arachnoid cap cells, whereas, the trabecular (fibroblast) cells formed the inner layers, which were separated by the basal lamina. Histologically, the fibrous and transitional meningioma subtypes had features similar to the fibroblast found in the deeper layers of the arachnoid, close to the subarachnoid space, whereas, the meningothelial subtype resembled the arachnoid cap cells of the outer layers. Therefore, Lee considered that differential leptomeningeal embryogenesis could result in the predominance of one cell type (i.e. the arachnoid cap cells and/or trabecular cells) in certain locations.[17] Finally, Chung et al. gave another explanation for histopathological variations of meningiomas, as he considered that meningiomas arose from polyblastic and functionally multipotent arachnoid cells.[18] The present study found that the high occurrence of meningiomas (such as Meningothelial, Fibroblastic, Transitional, and Psammomatous) at common anatomical sites (such as parasagittal, anterior parafalcine, cerebral convexity, and sphenoid ridge) led to a proportional decrease in the frequency of atypical and malignant meningiomas at such sites in comparison to the posterior fossa, base of skull, and intraventricular regions. The survival of Benign (WHO Grade I) was more than 95% as compared to the less than 25% survival of Malignant (WHO Grade III) meningiomas.

Conclusion

The present study finds a correlation between the histological type of meningeal brain tumors (meningiomas) and the location of origin. The uncommon types of meningiomas, Atypical (WHO Grade II) and Malignant (WHO Grade III), were found in high proportions at the jugular foramen, tentorium, sphenoid ridge, cerebellopontine angle, peritorcular, petroclival, orbital groove, posterior parafalcine, tuberculum sellae, and intraventricular regions. A mortality of 16.28% for the atypical histological type and 25.71% for the malignant type was mostly found in the above-mentioned areas. The survival of the benign or WHO Grade I types in the convexity, parasagittal, anterior parafalcine, and intraorbital areas was more than 95%. However, this study needs a further research-oriented study, hence, a specific histological examination has been established for meningiomas in specific locations, for specific treatment. If the preoperative milieu and cell of origin of a meningioma is known, the management might change to a better end in future because of this established correlation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Aisha, Huwa, Roh Ul, Saim ul, Abul-Adam and Nancy for their help.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Meningiomas: Historical perspective. In: Lee JH, ed. Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. London: Springer-Verlag; 2009. p. :3-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meningioma grading: An analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1455-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior fossa meningiomas. In: Sindou M, ed. Practical Handbook of Neurosurgery: From Leading Neurosurgeons. Vol 2. Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009. p. :181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and etiology of intracranial meningiomas: A review. J Neurooncol. 1996;29:197-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical experience with skull base approaches for foramen magnum meningioma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42:472-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Posterior fossa meningiomas: Correlation between site of origin and pathology. Rom Neurosurg. 2010;17:327-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology. In: Lee JH, ed. Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. London: Springer-Verlag; 2009. p. :11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foramen magnum meningiomas. In: Lee JH, ed. Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. London: Springer-Verlag; 2009. p. :449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Skull base tumors. In: Bernstein M, Berger MS, eds. Neuro-oncology: The Essentials (2nd ed). USA: Thieme; 2008. p. :323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebellar Convexity Meningiomas. In: Lee JH, ed. Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. London: Springer-Verlag; 2009. p. :457.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphoplasmacyte-rich meningioma at the foramen magnum. Br J Neurosurg. 2008;22:702-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chordoid meningioma of the foramen magnum in a child: A case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:623-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Foramen magnum meningioma: Dysphagia of atypical etiology. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:206-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meningeal tumors. In: Drevelegas A, ed. Imaging of Brain Tumors with Histological Correlations. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2002. p. :178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meningothelioma as the predominant histological subtype of midline skull base and spinal meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:60-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Falx meningiomas: Surgical results and lessons learned from 68 cases. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2007;42:276-80.

- [Google Scholar]