Translate this page into:

Neonatal meningitis complicating with pneumocephalus

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Pneumocephalus is a rare condition characterized by the presence of gas within the cranial cavity. This gas may arise either from a trauma, a tumor, a surgical, or a diagnostic procedure or occasionally from an infection. Pneumocephalus as a complication of bacterial meningitis, in absence of trauma or a procedure, is extremely rare, particularly in a newborn. A case of pneumocephalus occurring in a baby, suffering from neonatal meningitis, acquired probably through unsafe cutting and tying of the cord, is reported here. Cutting, tying, and care of the umbilical cord is of utmost importance to prevent neonatal infection as the same is a potential cause of serious anaerobic infections, besides tetanus.

Keywords

Gas producing organisms

meningitis

pneumocephalus

Introduction

Pneumocephalus is a rare condition characterized by the presence of gas within the cranial cavity. It may arise from trauma, tumors, following surgery or some diagnostic procedures and rarely from infection.[12] In the absence of injury and surgery, spontaneous pneumocephalus secondary to meningitis, caused by a gas producing organism, is rather a rare occurrence. We report here a case of pneumocephalus occurring in a neonate suffering from meningitis, who died within 48 hours of hospitalization.

Case Report

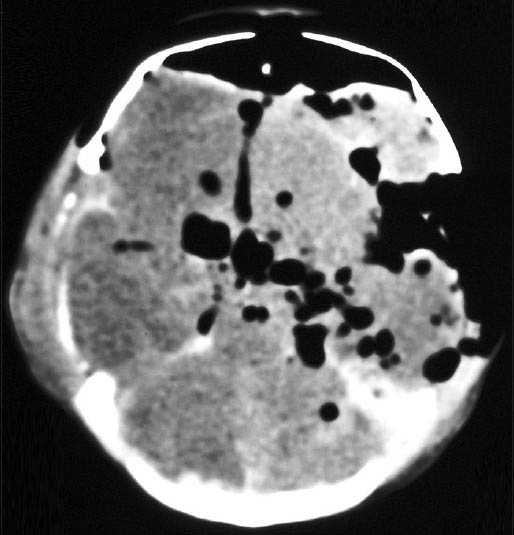

A 7-day-old male newborn was brought to the casualty with complaints of refusal to feed and progressive increase in head size for the last 3 days. In view of his critical condition, the baby was immediately put on ventilator with supportive management. History revealed that though the mother had received two doses of tetanus toxoid during the second trimester of pregnancy, and rest of her antenatal period was also uneventful, the baby had been home delivered wherein a blade and the common home thread had been used for cutting and tying the umbilical cord. The baby had cried immediately after birth and was on breastfeeding since then, but he started refusing feed from the fourth day onwards, besides a gradual increase in the head size. On examination, the baby was hypothermic, pale, and had an enlarged head (39 cm). The umbilical cord had fallen on the 5th day of life, but the area showed signs of inflammation. His heart rate was 130/min, respiration was irregular, and capillary refill time (CRT) was >3 seconds. His blood glucose was 33 mg/dL. Results of the laboratory investigations done on his blood were as follows: Hemoglobin (Hb) - 13.9 g/dL, total leukocyte count (TLC) - 6.800 × 103/μL with neutrophils (N) 75% and lymphocytes (L) 25%, platelets - 85 × 103/μL, C-reactive protein - 20 mg/dL, total serum bilirubin - 8 mg/dL (direct 4 mg/dL), urea - 20 mg/dL, creatinine - 0.8 mg/dL, sodium - 142 mmol/L, potassium - 5.6 mmol/L, prothrombin time - 30 s (control - 15 s), and activated partial thromboplastin time 42 s (control - 30 s). In view of the enlarged head, bulging anterior fontanel and widely spaced cranial bones, congenital hydrocephalus, intraventricular hemorrhage, septicemia with meningitis, and battered baby syndrome were thought of as possible conditions. As his neurosonogram showed air like densities, a plain computed tomography (CT) scan of brain was done which revealed diffuse pneumocephalus along with large amount of air in subdural and subgleal spaces, besides showing hemorrhages and meningeal enhancement in the region of posterior fossa [Figure 1]. The diagnosis was clear now, that we were dealing with a case of meningitis with pneumocephalus and there was hardly any other possible differential diagnosis.

- Computed tomography scan of brain: Tension pneumocephalus showing huge amount of air compressing the frontal lobes, with the “air bubble sign”

A lumbar puncture (LP) was then done and his cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed cells - 550/μL (with N - 85%, L- 15%), glucose - 35 mg/dL, and protein - 228 mg/dL; the CSF and blood cultures were negative. In view of his critical condition, the baby was put on vancomycin (20 mg/kg/dose q8h, intravenous (IV)), meropenem (40 mg/kg/dose q8h, IV) along with supportive management. An attempt to decompress tension pneumocephalus was also made by putting an 18 G needle in subgleal plane, from which air came out under pressure. However, despite all this, the condition of the baby failed to show any improvement and he succumbed within 48 h of being brought to the hospital.

Discussion

Pneumocephalus is usually associated with head trauma or tumor of the skull base; it may follow a neurosurgical or otorhinological procedure and rarely occurs spontaneously.[3] In a review of 290 patients of pneumocephalus, trauma was the principle etiological factor, being responsible for 73.9% of cases, other causes being tumors (12.9%) and surgical interventions (3.7%); infection accounted for 8.8% of cases only.[1] In the present case, there was no history of trauma, evidence of a tumor, or breech in sinus plates; as seen in CT. LP can also be ruled out as a cause as pneumocephalus was noticed on brain CT before doing LP. All this makes clear that pneumocephalus in the present case was secondary to meningitis, though no organism was grown on CSF culture. Meningitis caused by gas producing organisms, for example, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides fragilis, Escherichia coli, Klebseilla aerogenes, Enterobacter cloacae, and by mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection may cause pneumocephalus.[456] In the present case, no organism was grown either on CSF or blood culture. However, there was history of home delivery and using simple unsterilized blade and thread for cutting and tying the umbilical cord which is an indirect evidence of anaerobic or mixed infection, causing hematological dissemination. To the best of our knowledge, pneumocephalus secondary to infection occurring through an unclean umbilical ligation has not been reported. There was reported another interesting case of pneumocephalus, occurring in a 12-year-old girl, suffering from pneumonia and meningitis, in which staphylococcus was isolated from the pleural fluid, though not from the CSF.[7] In a majority of meningitis cases, no organism can be isolated on culture, the reason being the initiation of antibiotics before the investigations and the use of less refined laboratory techniques.[8] Moreover, anaerobic organisms fail to grow by usual laboratory methods as they require specialized microbiologic techniques.[9]

Treatment of pneumocephalus depends on the degree and progression of air collection and of course the etiology. Most cases resolve with conservative management, while surgical intervention is indicated in continued CSF leak or progression to a tension condition.[10] In the present case, needle decompression was done twice, though without bringing any improvement. The cause of death in this baby was due to raised intracranial tension secondary to meningitis and septicemia which was evident by abnormal respiratory pattern, dilated pupils with sluggish reaction, hypothermia, and increased capillary refill time.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to the management of SRMSIMS for their general support.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- The clinical features of pneumocephalus based upon a survey of 284 cases with report of 11 additional cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1967;16:1-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lumbar puncture associated with pneumocephalus: Report of a case. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:524-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Spontaneous” pneumocephalus associated with mixed aerobic-anaerobic bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:847-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gas-producing clostridial and non-clostridial infections. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147:65-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Spontaneous” pneumocephalus associated with aerobic bacteremia. Clin Imaging. 1989;13:134-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pneumocephalus consequent to staphylococcal pneumonia and meningitis. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6:84-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Other anaerobic infections. In: Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, Behrman RE, Stantan BF, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (18th ed). Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. p. :1234.

- [Google Scholar]