Translate this page into:

Vitamin D deficiency rickets presenting as pseudotumor cerebri

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Pseudotumor cerebri is a condition of elevated intracranial pressure in the absence of clinical, laboratory or radiological evidence of an intracranial space-occupying lesion. Various associations with pseudotumor cerebri have been made in literature. We report the case of a five-month-old female infant with vitamin D deficiency rickets, who presented with pseudotumor cerebri. Her cerebrospinal fluid examination was normal, with a high opening pressure of 330 mmH2O. Her computed tomography scan was normal. After lumbar puncture the anterior fontanelle came at level. Her investigations revealed vitamin D deficiency. She was started on acetazolamide, calcitriol sachets, and calcium supplements. She became asymptomatic in three days and was discharged. Through this case we wish to highlight this unusual presentation of vitamin D deficiency rickets appearing as pseudotumor cerebri.

Keywords

Acetazolamide

increased intracranial pressure

papilledema

pseudotumor cerebri

vitamin D deficiency

Introduction

Pseudotumor cerebri or benign intracranial hypertension is a rare syndrome characterized by increased intracranial pressure, with a normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cell count and protein content, as also a normal ventricular size, anatomy, and position.[1] Although pseudotumor cerebri can occur at any age in childhood, it is uncommon in infants.[2] Vitamin D deficiency is known to be the leading cause of nutritional rickets. Various unusual presentations of vitamin D deficiency rickets (VDDR) like stridor, fractures, seizures, and myelofibrosis have been described in children.[3] We herein report an infant with VDDR, who presented with pseudotumor cerebri and was managed successfully.

Case Report

A five-month-old female infant presented with vomiting, bulging fontanelle, irritability, and refusal to feed, since one day. There was no history of fever, convulsion, bowel/bladder complaints, drug intake, rash or otorrhea. She was born of a non-consanguineous marriage and her birth, family, and developmental history were normal. She was exclusively breastfed. On examination, she was hemodynamically stable. Her weight, head circumference, and length were normal. She had chest beading, wide wrist, and a bulging wide anterior fontanelle. The fundus examination revealed early papilledema. She had mild hepatosplenomegaly due to visceroptosis. The liver was palpable 3 cm below the costal margin in the midclavicular line, with a span of 5.5 cm. The rest of the systemic examination was normal. Investigations revealed a normal hemogram. Her arterial blood gases, renal function, and serum electrolytes were normal. Serum calcium was 6.1 mg/dL, inorganic phosphorous 2.5 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 1084 IU/L, serum parathormone 430 pg/ml (N 12-72), 25-OH vitamin D 3.03 ng/ml (N 4012-100). The cerebrospinal fluid examination (CSF) was normal with a high opening pressure of 330 mmH2O. Her computed tomography scan was normal. After lumbar puncture the anterior fontanelle came at level. The patient's mother had not taken calcium supplements during the antenatal period. She was a vegetarian and had no symptoms or signs of vitamin D deficiency. Her serum calcium was 8.2 mg/dL, inorganic phosphorous 3.3 mg/dL, and alkaline phosphatase 787 IU/L. Her vitamin D levels and parathormone assay could not be done due to financial constraints. A final diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri due to vitamin D deficiency was made. The patient was started on acetazolamide (15 mg/kg/day), calcitriol sachets, and calcium supplements. She became asymptomatic in three days and was discharged. On follow up after a year, she is asymptomatic and well.

Discussion

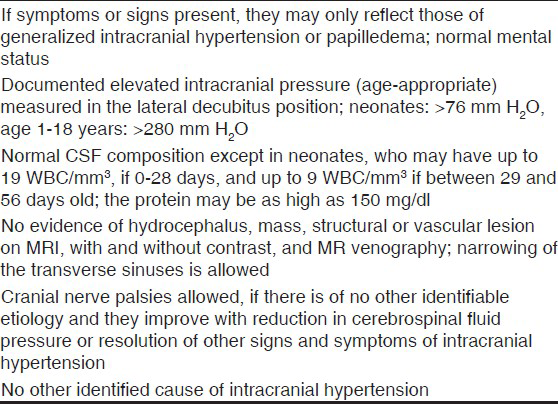

There are many explanations for the development of pseudotumor cerebri including alterations in CSF absorption and production, cerebral edema, abnormalities in cerebral vasomotor control, and cerebral blood flow and venous obstruction.[1] The most common presenting symptom is headache. Other frequent manifestations include diplopia (from cranial nerve VI palsy), blurred vision, nausea and/or vomiting, altered light perception, papilledema, and decreased visual acuity.[12] Patients with pseudotumor cerebri have normal levels of consciousness and functioning. The presence of focal neurological signs indicates a process other than pseudotumor cerebri.[1] The diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri is suspected on the basis of the history and examination. Previously, the Modified Dandy criteria were used for diagnosis of pseudotumor cerebri in both adults and children. Rangwala and Liu proposed a new diagnostic criteria for pseudotumor cerebri in prepubertal children, as presentation in young children appears to be different when compared with that in adolescents and adults.[4] In the setting of newly published reference ranges for CSF in children, Ko et al. have modified the diagnostic criteria for pediatric pseudotumor cerebri [Table 1].[2] Various associations with pseudotumor cerebri have been reported, which have been listed in Table 2.[1] It is not clearly known whether these are simply chance associations or really related to the pathophysiology of pseudotumor cerebri. Also, very little has been described in literature regarding the contribution of each as the etiology. As other conditions associated with pseudotumor cerebri were excluded in our case, we are justified in attributing her symptoms to VDDR. Salaria et al. have described a similar case in a four-month-old infant. However, the infant had presented with hypocalcemic convulsions in contrast to our patient, who had irritability and bulging fontanelle.[5] De Jong et al. and Hanafy et al. have described infants who had pseudotumor cerebri and nutritional rickets. However, in contrast to our case, the bulging fontanelle in their patients persisted for several months even after starting treatment.[67]

The exact mechanism of pseudotumor cerebri in VDDR is unknown and various hypotheses have been put forward. The derangement of calcium or phosphorous metabolism may be responsible through alteration in cellular energy utilization, membrane structure and function or intercellular ion concentration.[8] As per another hypothesis, stimulation of the adenylate cyclise system in the choroid plexus results in CSF hypersecretion. Nathanson showed that when divalent cations (including Ca ++) are removed from the choroid plexus tissue by chelating agents, the basal and isoproterenol stimulated adenylate cyclise activity is increased.[9] This may result in CSF hypersecretion. Sambrook et al. studied CSF absorption in a patient with primary hypoparathyroidism, papilledema, and epilepsy.[10] They found a marked reduction of CSF transport into the plasma, which returned to normal after correction of the hypocalcemia. Baker et al. studied the pathological changes causing a reduction in CSF absorption.[11] Using the giant squid axon they demonstrated a reduction in the rate of efflux of intracellular sodium in the presence of decreased extracellular calcium. The increase in intracellular sodium and water in the arachnoid villi interferes with the movement of CSF.

The main aim of the management of pseudotumor cerebri is discovery and treatment of the underlying cause. Treatment of the metabolic cause usually results in reversal of symptoms of the pseudotumor cerebri within one week. The pseudotumor cerebri is usually a self-limited condition, but delayed treatment can lead to optic atrophy and blindness.[12] Various methods like serial lumbar punctures, acetazolamide (10-30 mg/kg/day), and corticosteroids have been tried with success.[1] Rarely, a lumboperitoneal shunt, subtemporal decompression or optic nerve sheath fenestration is necessary.[12]

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware of the different ways in which vitamin D deficiency can present, to ensure its early diagnosis and treatment. Also, vitamin D deficiency rickets should be considered in the differential diagnosis of infants presenting with pseudotumor cerebri.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Dean of their institute for permitting them to publish this manuscript.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Pseudotumor cerebri. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, Stanton FB, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (18th ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2008. p. :2525-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri) Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;74:381-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myelofibrosis: An unusual presentation of vitamin D-deficient rickets. Eur J Pediatr. 1999;158:828-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rickets presenting as pseudotumour cerebri and seizures. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign intracranial hypertension in vitamin D deficiency rickets associated with malnutrition. J Trop Pediatr Afr Child Health. 1967;13:19-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beta-Adrenergic-sensitive adenylate cyclase in choroid plexus: Properties and cellular localization. Mol Pharmacol. 1980;18:199-209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cerebrospinal fluid absorption in primary hypoparathyroidism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40:1015-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of calcium on sodium efflux in squid axons. J Physiol. 1969;200:431-58.

- [Google Scholar]