Translate this page into:

What is next after transfer of care from hospital to home for stroke patients? Evaluation of a community stroke care service based in a primary care clinic

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Context:

Poststroke care in developing countries is inundated with poor concordance and scarce specialist stroke care providers. A primary care-driven health service is an option to ensure optimal care to poststroke patients residing at home in the community.

Aims:

We assessed outcomes of a pilot long-term stroke care clinic which combined secondary prevention and rehabilitation at community level.

Settings and Design:

A prospective observational study of stroke patients treated between 2008 and 2010 at a primary care teaching facility.

Subjects and Methods:

Analysis of patients was done at initial contact and at 1-year post treatment. Clinical outcomes included stroke risk factor(s) control, depression according to Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9), and level of independence using Barthel Index (BI).

Statistical Analysis Used:

Differences in means between baseline and post treatment were compared using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon-signed rank test. Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results:

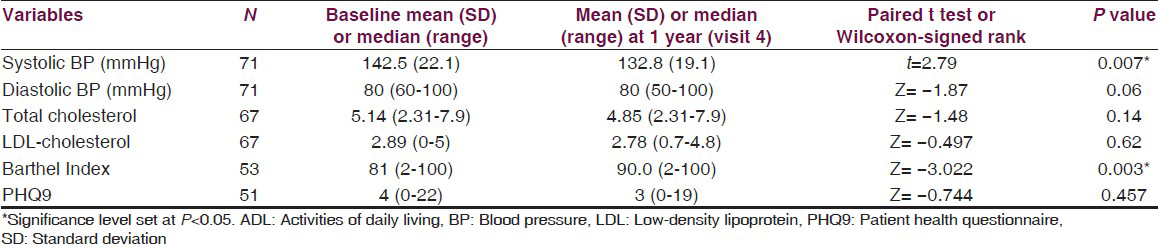

Ninety-one patients were analyzed. Their mean age was 62.9 [standard deviation (SD) 10.9] years, mean stroke episodes were 1.30 (SD 0.5). The median interval between acute stroke and first contact with the clinic 4.0 (interquartile range 9.0) months. Mean systolic blood pressure decreased by 9.7 mmHg (t = 2.79, P = 0.007), while mean diastolic blood pressure remained unchanged at 80mmHg (z = 1.87, P = 0.06). Neurorehabilitation treatment was given to 84.6% of the patients. Median BI increased from 81 (range: 2−100) to 90.5 (range: 27−100) (Z = 2.34, P = 0.01). Median PHQ9 scores decreased from 4.0 (range: 0−22) to 3.0 (range: 0−19) though the change was not significant (Z= −0.744, P = 0.457).

Conclusions:

Primary care-driven long-term stroke care services yield favorable outcomes for blood pressure control and functional level.

Keywords

Long-term stroke care

poststroke

primary care

Introduction

Stroke is a common global health care problem, often resulting in disabling complications. Each year, 15 million people suffer from stroke worldwide, of whom; 5 million survive with permanent disabilities.[1] For stroke survivors and their families, the real challenges in living with stroke problems arise once the patients are transferred from hospital to home. Post discharge care has been fragmented and poorly coordinated even in more economically developed countries.[23] Compared to organized inpatient stroke care, which has been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality,[4] determining ideal and effective post discharge care delivery has been difficult for developing countries.[5678]

However, with nearly 85% of global stroke deaths occurring in developing countries,[9] these countries need to overcome challenges such as limited access to secondary prevention, increase in ageing population, and the rise in cardiometabolic risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity to ensure optimal care for stroke survivors. Hence, primary care teams will need to come up with feasible yet effective post discharge stroke care within the limited health care services in these underserved communities.

Different approaches have been used to provide comprehensive care specifically targeted to the needs of stroke patients and their carers. Previously reported approaches to providing post discharge stroke care includecase-based management, disease-management program, and multidisciplinary integrated care.[71011] However, the difficulty to achieve standardized care was related to variations in healthcare service systems and problems in accessing specialist stroke care service.[7812] Upon discharge from specialist care, stroke survivors and their families often end up consulting a general practitioner or the primary care team to help solve their problems more than any other health service provider.[13] These problems may be stroke-related, new medical problems, or unmet needs.[1314] Although guidelines had advocated long-term stroke care that involves a multidisciplinary approach,[1516] community stroke care still is a single-based service. The exact involvement of the primary care team in long-term stroke outcomes, however, remains unclear.[17]

In Malaysia, most stroke patients return home to stay with their families once they are discharged from hospitals. This is usually after a short stay in hospital after the acute ischemic event.[18] In general, patients will be given instructions for further follow up-either at the Neurology or Internal Physician's Outpatient Clinics (whichever is available) or to the nearest public funded Health Centre. The latter is usually in a form of a passive referral that informs the attending doctor of the transfer of care from hospital to primary care. Currently, even the local clinical practice guideline does not specifically address problems of long-term stroke patients and their carers at primary care level.[19] Little is known about the outcomes of long-term stroke patients living at home in the Malaysian community or the burden of post stroke care in primary care centers. Our study reports on outcomes in long-term stroke patients who were managed at a primary care facility and describes the process of care, which takes place in this type of service believed to be the first of its kind in Malaysia. It is hoped that the findings of this study will form the basis for further development of an integrated care program at primary care level for managing post stroke patients living at home in the community.

Subjects and Methods

The long-term stroke clinic

The Long Term Stroke Clinic (LTSC a.k.a ‘Klinik Lanjutan Strok’) is a unit in a primary care clinic (‘Pusat Perubatan Primer Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, PPPUKM) that provides follow-up care for stroke patients in the Cheras locality, approximately 23 km north east of Putrajaya, administrative capital of Malaysia. Referrals are accepted from any multidisciplinary stroke care team member (i.e., neurology, neurosurgical, or rehabilitation service) or from either public or private general practitioners from the surrounding areas.

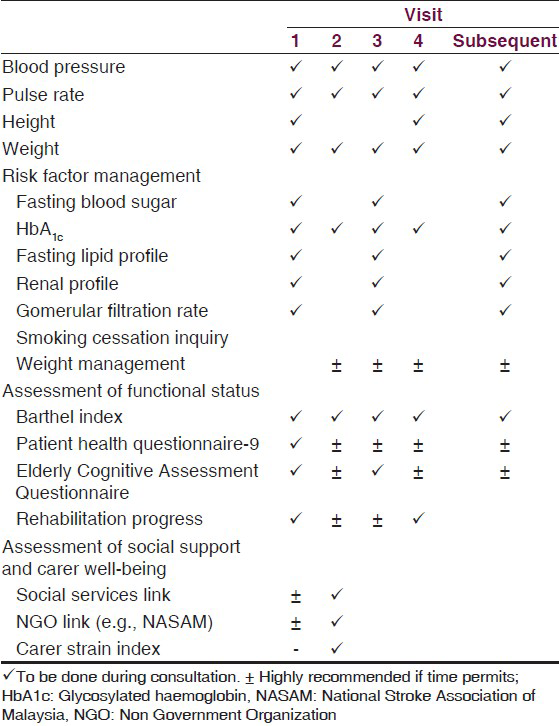

The clinic is held once a week in a teaching primary care center, focused on secondary risk prevention, screening for stroke-related complications, and new emerging problems, coordinating further rehabilitation therapy and also facilitating reintegration back into the community using community-based support services as well as social welfare aids. In addition, carers are screened for caregiver strain and those identified as having stress or any medical problems are also managed in the clinic. Family counseling is offered when required to promote better compliance to treatment for both patient and carer or family member. Please refer to Table 1 for details on the management care plan.

The clinic is managed by a stroke coordinator, that is, a registered nurse who is responsible for coordinating appointments and home visits, providing health education for stroke patients and carers, and maintaining a registry of LTSC patients. The team comprises of a stroke rehabilitation consultant, a family medicine consultant, two nurses (includes the stroke coordinator), and a Clinic aide. Two post graduate trainees in Family Medicine also assist the team on a rotational basis. Patients are managed following a long-term stroke care manual which was developed by the team members using evidence-based medicine, literature, and clinical practice guidelines. This manual is regularly reviewed as per evidence-based recommendations from current literature findings.

Patients are seen by appointment with priority given to cases that had not had any medical checkup after discharge. A complete history and thorough physical examination is done during the first consultation to determine the baseline functional status. The team will then prioritize and discuss the management plan with the patient and their carer. The priority during this first consultation would be to determine treatment goals for stroke, to control for risk factor(s), and to decide whether further rehabilitation is required. If further intervention by the multidisciplinary care team is required, patients will be referred. Carer issues will be addressed during the second or third clinic visit once rapport is better established and will be prioritized based on the nature of the problem.

Patients are reviewed on a 3-4 months interval basis with more frequent visits in case of acute problems associated with the stroke condition, for example, urinary tract infection, pressure sores, or uncontrolled diabetes that requires close monitoring [Table 1]. Regular monitoring aims at ensuring treatment targets are met, periodic functional status assessments (Barthel Index, BI) detects deterioration in activities of daily living,[20] screening for depression (using Patients’ Health Questionnaire, PHQ9)[2122] and dementia (using Elderly Cognitive Assessment Questionnaire, ECAQ),[23] drug compliance and polypharmacy, social support (linked to local social welfare for potential benefits/aids), and community-based support groups for patient and their carers. Each month, the LTSC team meets and discuss problematic cases either patient or carer-related or issues of care coordination between multidisciplinary care team members. Team members work out solutions and provide necessary measures to rectify the problems. Goals were determined while considering patients’ and or carers’ wishes and opinions. The patients are followed-up for a total duration of 2 years. At the end of this period, the patients and their carer(s) will be referred back to a general practitioner of their choice. Patients who were previously under the general outpatient care pool of the same primary care clinic will be returned back to that unit for follow-up. Details of the treatment given, goals achieved, and monitoring recommendations are given to the attending general practitioner taking over the care of the patient. Communication, that is, feedback responses between physicians involved in transfer of care cases are actively maintained at all times.

A written informed consent was obtained from all patients (at baseline visit) or their principal carer where required.

Study design

We designed a prospective observational study of stroke patients attending LTSC from 1st September 2008-31st December 2010. The medical records of all patients registered during this period were included for analysis. Patients with a recorded diagnosis of stroke by radiographical diagnosis, diagnosis confirmed by a neurologist, or a combination of these methods were included in the study. We excluded patients who were diagnosed as transient ischemic attack and aged less than 18 years at time of diagnosis.

A data collection form was used to extract data from the medical records at initial intake and subsequent four clinic visits. Visit 4 coincides with 1 year post-program enrolment for all patients.

Descriptive analyses using mean, median, and proportions were used. Differences in means between baseline and post treatment were compared using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon-signed rank test. Significance level was set at 0.05.

Intention to treat analysis was used to prevent bias introduced by missing data and patient drop-out rates (i.e., patients who did not turn up on scheduled review visit date). For patients who missed the final assessment, the “last observation carried forward” method was used. Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®) software version 20.

Permission to reproduce data was obtained from the clinic coordinator and the Dean and Director of the UKM Medical Centre. This study was a part of a PhD project and obtained approval from the ethics and research committee of the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre. The project received funding from the university's research grant, that is, Geran Universiti Penyelidikan. (Research ID: UKM-GUP-2011-327).

Results

We traced 106 case records registered in the LTSC registry during the study period. Three patients had died before appointment date and 12 records were untraceable. Ninety-one patients were admitted into the study.

All patients were alive and remained under follow-up at the same clinic during the period of study.

Patient profile

The overall mean age of the patients at diagnosis was 62.9 [standard deviation (SD) 10.9] years. Male patients predominated (58.2%). Most patients were referred from Internal Physician's clinic (33.0%), general practitioners (22.0%), followed by Combined Stroke Rehabilitation Clinic (20.9%), self-referral by patients and/or carers (7.7%) and Neurosurgery clinic (5.5%). The source of referral for 11% of the patients could not be determined. The median time taken for contact with primary care provider after discharge from hospital or after acute stroke was 4.0 months [interquartile range (IQR) 9.0].

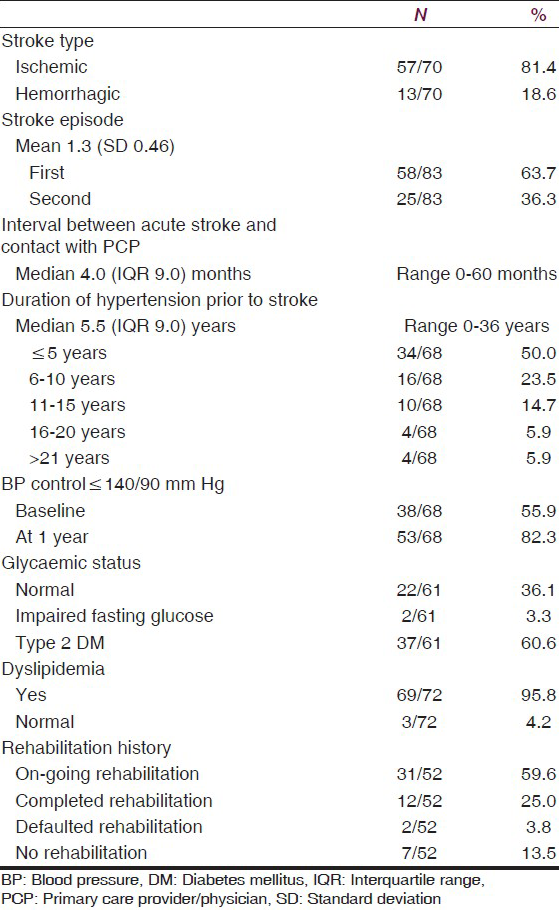

From Table 2, we note that the majority of patients had ischemic stroke and that almost a third were recurrent episodes. Almost three quarters had background history of hypertension, with a median duration of 5.5 years (IQR 0−36). The majority of patients (95.8%) had dyslipidemia, while slightly more than half of the patients were receiving treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus. As for smoking status, 15% of patients continued to smoke despite their stroke.

Stroke risk factor(s) control

There was improvement in the proportion of patients who had blood pressure readings of ≤140/90 mmHg at 1 year follow-up (55.9% vs. 82.3%) [Table 2]. The change in median systolic blood pressure was found to be significant when further analyzed (t = 2.79, P = 0.07). Diastolic blood pressure, lipid level readings, that is, total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol plus depression did not show significant improvements after one year [Table 3].

Stroke rehabilitation and functional status

Almost 60% of the patients were still undergoing rehabilitation, while a quarter had completed rehabilitation [Table 2]. Concurrently, the functional status of patients showed an increasing trend over the 1-year period in the median BI scores [Table 3].

Depression

At baseline, 80.4% (41/51) of the patients had minimal symptoms of depression (PHQ9 scores ≤ 9), 9.8% (5/51) with minor depression (PHQ scores10−14), 7.8% (4/51) major depression (PHQ scores15−19) and 2.0% (1/51) with major depressive symptoms (PHQ score ≥ 20). However, when comparing median PHQ9 scores at baseline and after 1 year, the differences were not statistically significant [Table 3].

Discussion

This study has given an account of how a structured post stroke care program based in primary care was able to provide monitoring for secondary stroke prevention as well as managing further rehabilitation needs for stroke patients residing at home.

Most studies on long-term stroke care were usually specialist-driven services with general practitioners’ support[24252627] or concentrated on rehabilitation needs only.[12] Our center provided a different service, in which the LTSC was developed to combine the elements of secondary stroke prevention together with rehabilitation aiming to facilitate seamless transfer of care from hospital to home. In countries where access to specialized stroke care and social service support is limited, a primary care based long-term stroke care service offers an alternative or only option for stroke survivors residing at home in the community.

In terms of stroke risk factors, our study population had a high prevalence of diabetes (60.6%) and hypertension (74.7%), indicating a need for secondary prevention. Hypertension control among stroke patients is one of the most modifiable risk factors to prevent recurrence.[28] The proportion of patients who had blood pressure ≤140/90mmHg after 1 year follow-up at LTSC showed an increase of 22.5% in proportion. Our findings were better compared with the findings of Girot et al.,[29] who recorded only 58% of post ischemic stroke patients having a blood pressure of ≤140/90 at follow-up. The reduction in systolic blood pressure over a period of 1 year after follow-up was significant (P < 0.01). We hypothesize that the provision of structured care plan at LTSC has a positive impact on risk factor monitoring and carrying out secondary prevention measures.

Diabetes is a well-known risk factor for stroke but its impact on stroke incidence rates is inconclusive.[3031323334] Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes across all ages around the world, the significance of diabetes influencing stroke incidence as a risk for stroke is a cause for concern. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus in this country (16.4% in 2006) and related risk factors such as dyslipidemia and coronary heart disease are possible contributing factors for stroke incidence.[35] In the Third Malaysian National Health and Morbidity Survey in 2006, 3.4% of diabetic patients were reported to have had a stroke event.[36] Our study showed that diabetes mellitus affected almost a quarter of the study population particularly stroke survivors between 50 and 64 year olds. This finding is similar to stroke patients in The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study where risk for ischemic stroke was greater among diabetics aged less than 65 years.[37]

The emphasis on rehabilitation of long-term stroke patients is to encourage further rehabilitation and community reintegration. Further rehabilitation has been incorporated in many guidelines as a component of long-term stroke management.[151638] However, this aspect is often neglected by primary care team due to lack of awareness and coordination with rehabilitation teams in the hospitals. However, in our study, more than 80% of our patients have had rehabilitation. This may be due to structured management and better coordination of care between the stroke multidisciplinary care team and the primary care team. Significant improvements of median BI scores over a 12-month period was noted (z=−3.022, P = 0.003). The median scores at baseline indicated that patients started off being moderately dependant on carers and slightly dependant after 1 year. We used the classification recommended by Shah and colleagues[39] which categorized the patients according to their level of independence after a stroke.

As such, our findings support recommendations that upon early discharge from hospital, patients with mild or moderate impairment should continue to have rehabilitation in community setting provided by a multidisciplinary team with expertise.[164041]

Post stroke depression affects almost one third of stroke patients[42] and is the most common neuropsychiatric consequence of stroke.[43] Early detection of post stroke depression is advised to prevent more significant impairments in daily activities, increase usage of health services and even institutionalization of stroke patients.[44] However, no reliable evidence-based clinical management exists and choice of assessment tools is unclear. We chose the PHQ-9 as our screening tool as it has been validated for use in primary care setting as well as stroke patients undergoing stroke rehabilitation.[21] Almost 10% of patients seen at first contact had symptoms of major depression but number of patients declined during the 1-year period while at primary care. To ensure that missing data did not influence the findings (i.e., Type 1 errors), we reanalyzed the data using intention to treat analysis principles. We found the results were not statistically significant (z = −0.744, P = 0.457). Patients in our clinic who present with symptoms of clinical depression and have PHQ9 scores of 9 and more were considered for pharmacological treatment with escitalopram. Patients were monitored accordingly throughout treatment period which was given no longer than 6 months. Part of the reason for the missing data may be due to failure to test or record PHQ9 scores during the decision to discontinue pharmacological treatment for patients who have showed clinical improvement. We concur with the findings of Joubert et al.,[25] who concluded that a shared care model is beneficial in detection as well as treatment of depression.

Our care plan was designed to deliver comprehensive long-term stroke within limited time constraints in a busy primary care practice. Roles and tasks of other primary care team members are identified to facilitate smooth delivery of service. Priority issues are recognized and addressed at each contact with the primary care team. We believe this method allows delivery of secondary stroke prevention measures in a comprehensive and “opportunistic” manner with each contact at the general practitioner's practice. Rehabilitation must be incorporated into any long-term stroke care service provision. The primary care physicians need to have some basic knowledge on stroke rehabilitation, basic indications for referral, and need to maintain good communication with the rehabilitation team.

The LTSC is a stand-alone entity in our setting and adopts an open policy in receiving patients with stroke at varying stages of recovery or “prevalent stroke” as described by Hare.[45] We feel that an established care pathway linking the post stroke patient to the primary care team at the appropriate period will improve delivery of long-term stroke care. This mechanism is currently lacking and mainly results in chance encounters with the primary care service.

Our study showed that there was a median of 4-month delay between the acute stroke episode and contact with a primary care provider. This duration is not acceptable in our opinion as risk of recurrent stroke is highest within first 6 months after the first episode.[464748] In recent recommendations for care of post stroke patients in the UK, review intervals at 6 weeks, 6 and 12 months are advised after discharge from hospital care.[49] The delay in contact with the primary care team suggests that there is gap in coordination of post stroke care after discharge from hospital care.

While most longitudinal studies on stroke patients usually discuss clinical outcomes of stroke patients at different stages of stroke recovery, our study concentrates on the outcomes of patients after 1 year of management at primary care. As mentioned earlier, the absence of a coordinated transfer protocol has resulted in the patients being at various stages of stroke recovery at baseline. However, as primary care physicians, this appears to be the norm in our practice, where patients arrive at their convenience and are almost never discharged from our practice unless “naturally discharged” at death.

The establishment of a care pathway for long-term stroke patients in the community will also help to reduce congestion at tertiary care centers, which currently continues to provide this service in this country.

Limitations

While our care pathway attempts to provide comprehensive post stroke care for patients residing at home in the community, this service is only accessible to patients who are ambulant or have reliable transportation to access the health centre.

The large number of missing data in the medical records affected the analysis of the some variables in this study. This was due to the various methods in which the information was stored, for example, medications and blood investigation results of the patients were stored in a computerized health information system, while medical records and screening tools/scores were handwritten and in hard copy versions. Improper filing of and/or missing score sheets complicated data retrieval. In cases where certain problems were “clinically resolved” and treatment discontinued, for example, depression, the monitoring scores, thatis, PHQ9 were not recorded at exit. The missing data may have also occurred when the patients returned to the clinic as scheduled but were not seen by the doctors at LTSC specifically but were seen by other primary care doctors at the same premise. As such, there was no actual “drop out cases” for our study.

Recommendations

Our study monitored the outcomes of long-term stroke patients up to duration of 1 year under primary care, monitoring patients at various stages after acute stroke. In healthcare settings where in-patient rehabilitation facilities, community rehabilitation hospitals and specialist stroke services are not available, provision of long-term stroke care based at primary care provides an alternative.

To determine effectiveness of intervention, a randomized trial comparing post stroke patients undergoing structured care (i.e., care pathway) compared with “conventional care” in a prospective trial is recommended. Its cost-effectiveness should also be determined to enable wider implementation of such services, particularly in countries where resources are limited.

Conclusions

A primary care-driven long-term stroke care service which provides rehabilitation and post stroke management at community level yields favorable outcomes for long-term stroke patients residing at home especially in control of systolic hypertension and functional ability.

Acknowledgments

We wish to record our appreciation for the dedication and assistance provided by our Long-term Stroke Clinic staff, SRN Asriah Ishak and SRN Zazalina Muhammad during the trial period.

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- World Heart Federation. The global burden of stroke. Available from: http://www.world-heart-federation.org/cardiovascular-health/stroke

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimizing stroke systems of care by enhancing transitions across care environments. Stroke. 2008;39:2637-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of hospital and outpatient care after stroke or transient ischemic attack: Insights from a stroke survey in the Netherlands. Stroke. 2006;37:1844-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- How do stroke units improve patient outcomes?. A collaborative systematic review of the randomized trials. Stroke Unit Trialists Collaboration. Stroke. 1997;28:2139-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ineffective secondary prevention in survivors of cardiovascular events in the US population: Report from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1621-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developing a primary care-based stroke service: A review of the qualitative literature. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:137-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: A review of systematic reviews. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17:141-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidisciplinary care planning in the primary care management of completed stroke: Asystematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: A systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:355-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrated care: Meaning, logic, applications, and implications: A discussion paper. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e12.

- [Google Scholar]

- A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:478-88.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. What are the components of effective stroke unit care? Age Ageing. 2002;31:365-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stroke services in general practice: Are they satisfactory? Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47:787-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measuring outcomes in the longer term after a stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:918-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Stroke Foundation. Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. 2010. Available from: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/cp126.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Stroke Network and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care Update. 2010. (4th ed). 2012–2013 update Available from: http://www.strokebestpractices.ca/index.php/prevention-of-stroke

- [Google Scholar]

- Secondary stroke prevention: Review of clinical trials. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:II25-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors and complications of acute ischaemic stroke patients at Hospital Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (HUKM) Med JMalaysia. 2003;58:499-505.

- [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Medicine Malaysia, Malaysian Society of Neurosciences, Ministry of Health Malaysia. Clinical Practice Guidelines : Management of Ischaemic Stroke. 2012. (2nd edition). Available from: http://www.acadmed.org.my/index.cfm? and menuid = 67

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance of the PHQ-9 as a screening tool for depression after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:635-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the malay version brief patient health questionnaire (PHQ9) among adult attending family medicine clinics. Int Med J. 2005;12:259-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- The NUH Memory Clinic. National University Hospital, Singapore. Singapore Med J. 1997;38:112-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cluster randomized controlled trial of a patient and general practitioner intervention to improve the management of multiple risk factors after stroke: Stop stroke. Stroke. 2010;41:2470-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Integrated care improves risk-factor modification after stroke: Initial results of the integrated care for the reduction of Secondary stroke model. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:279-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective study of acute cerebrovascular disease in the community: The Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project 1981-86. 1. Methodology, demography and incident cases of first-ever stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:1373-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perth Community Stroke Study: Design and preliminary results. Clin Exp Neurol. 1990;27:125-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of secondary vascular prevention in practice after cerebral ischemia and coronary heart disease. J Neurol. 2004;251:529-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of population-based models of risk factors for TIA and ischemic stroke. Neurology. 1999;53:532-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stroke in patients with diabetes. The Copenhagen stroke study. Stroke. 1994;25:1977-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of hospitalized stroke in men enrolled in the Honolulu Heart Program and the Framingham Study: A comparison of incidence and risk factor effects. Stroke. 2002;33:230-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-insulin-dependent diabetes and its metabolic control are important predictors of stroke in elderly subjects. Stroke. 1994;25:1157-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for death from stroke. Prospective study of the middle-aged Finnish population. Stroke. 1996;27:210-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Third National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS III) 2006. Institute for Public Health (IPH); 2008. p. :208-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- prevalence of diabetes in the Malaysian National Health Morbidity Survey III 2006. Med J Malaysia. 2010;65:173-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of ischemic stroke in patients with diabetes: The Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study. DiabetesCare. 2005;28:355-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- SIGN (2010). Management of patients with stroke: Rehabilitation, prevention and management of complications, and discharge planning A national clinical guideline [Internet] Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign118.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:703-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for management of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack 2008. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;25:457-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early Supported Discharge Trialists. Early supported discharge after stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:103-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frequency of depression after stroke: A systematic review of observational studies. Stroke. 2005;36:1330-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Management of depression in elderly stroke patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:539-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- What do stroke patients and their carers want from community services? Fam Pract. 2006;23:131-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blood pressure reduction and secondary prevention of stroke and other vascular events: A systematic review. Stroke. 2003;34:2741-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term prognosis after a minor stroke: 10-year mortality and major stroke recurrence rates in a hospital-based cohort. Stroke. 1998;29:126-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term risk of recurrent stroke after a first-ever stroke. The Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1994;25:333-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Life after Stroke: Commissioning guide. United Kingdom: National Health Service (NHS); Available from: http://www.londonhp.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Life-After-Stroke.pdf

- [Google Scholar]