Translate this page into:

Endoscopic assisted microsurgical removal of cerebello-pontine angle and prepontine epidermoid

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Cerebello-pontine(CP) angle and prepontine epidermoid tumors are challenging lesions because they grow along the subarachnoid spaces around the very important neurovascular structures and often extend into the supratentorial compartment. They have typically been removed through a variety of anterolateral, lateral, and posterolateral cranial base microsurgical approaches. Sometime they were removed by the endoscope-assisted microneurosurgical (EAM) techniques. Here we report a CP angle and preontine epidermoid tumor extended to supratentorial compartment presented with trigeminal neuralgia that was removed by pure endoscopic visualization through retrosigmoid retromastoid lateral suboccipital approach. (The method of using endoscope along with surgical instruments passing along the sides of endoscope is termed as Endoscope-Controlled Microsurgery–ECM.) So far our knowledge, in the literature this type of report is probably very rare.

Keywords

CP angle

Endoscope-Controlled Microsurgery

endoscopic removal

prepontine epidermoid

supratentorial extension

Introduction

It has been found out that 0.2% to 1% of all primary intracranial tumors are epidermoid tumor. Intracranial epidermoid tumors are histologically benign, slow-growing, congenital neoplasms of the central nervous system.[1] CP angle and prepontine epidermoid tumors are challenging lesions because they grow along the subarachnoid spaces around the very important neurovascular structures and often extend into the supratentorial compartment.[2] They have typically been removed through a variety of anterolateral, lateral, and posterolateral cranial base microsurgical approaches.[3] Sometimes they are removed by endoscope-assisted microneurourgical techniques.[2–4] So far our knowledge, in the literature pure use of endoscope (i.e. ECM) in the removal of prepontineepidermoid had not reported. Here we report a preontineepidermoid tumor extended to supratentorial compartment presented with trigeminal neuralgia that was removed by pure endoscopic visualization through retrosigmoid retromastoid lateral suboccipital approach.

Case Report

Case description

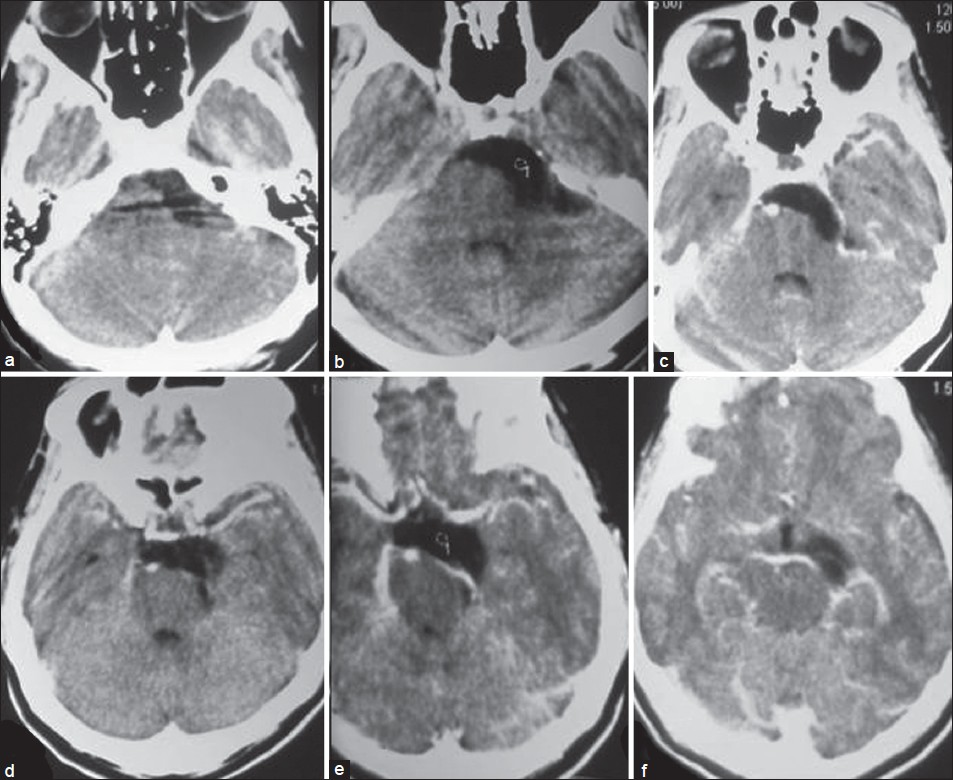

A right-handed 45-year- old man presented with headache and progressively increasing left-sided trigeminal neuralgia involving all three division of 5th nerve for the last 2 years. Initially the attack of neuralgic pain was less frequent and had been easily controlled by carbamazepin. But later it became more frequent and intractable. He had no history of vomiting, visual disturbance, unconsciousness, convulsion, or other complaints that suggest cranial nerves or cerebellar dysfunctions. His physical examination including neurological examination was absolutely normal. CT scan of brain showed a hypodense left CP angle and prepontine mass lesion with supratentorial extension into basal cistern that did not enhance after contrast injection [Figures 1a–f]. There was lobulation pattern in its capsule suggesting epidermoid tumor. MRI of brain showed a space occupying hypointense mass (T1W images) in the prepontine area (left>right) with supratentorial extension into interpeduncular cistern that did not enhance after contrast injection. It became hyperintense in T2W images and FLAIR images differentiated it from cerebro spinal fluid (CSF).

- Preoperative CT scan of brain serial axial sections (a-f) showing hypodence epidermoid tumor in left cerebello-pontine angle and prepontine area as well as supratentorial extension with displacement of brainstem

Operative techniques

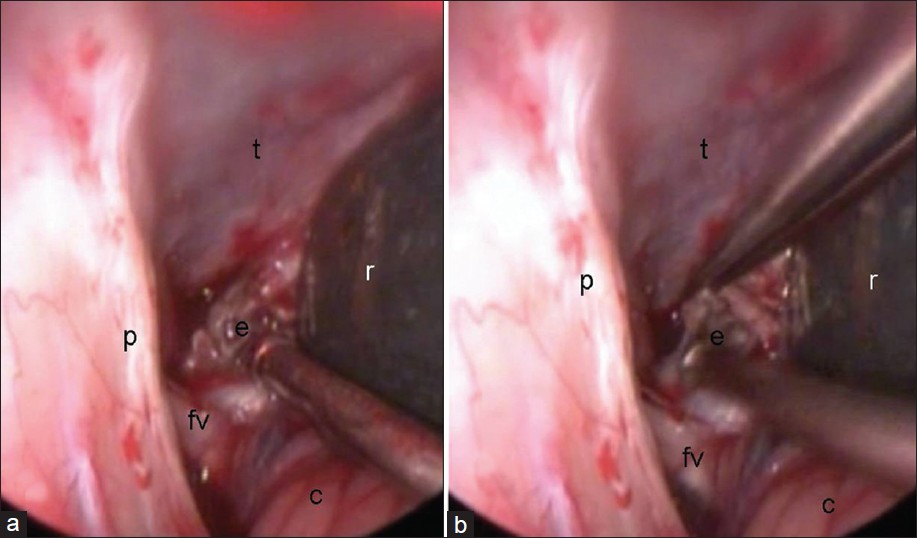

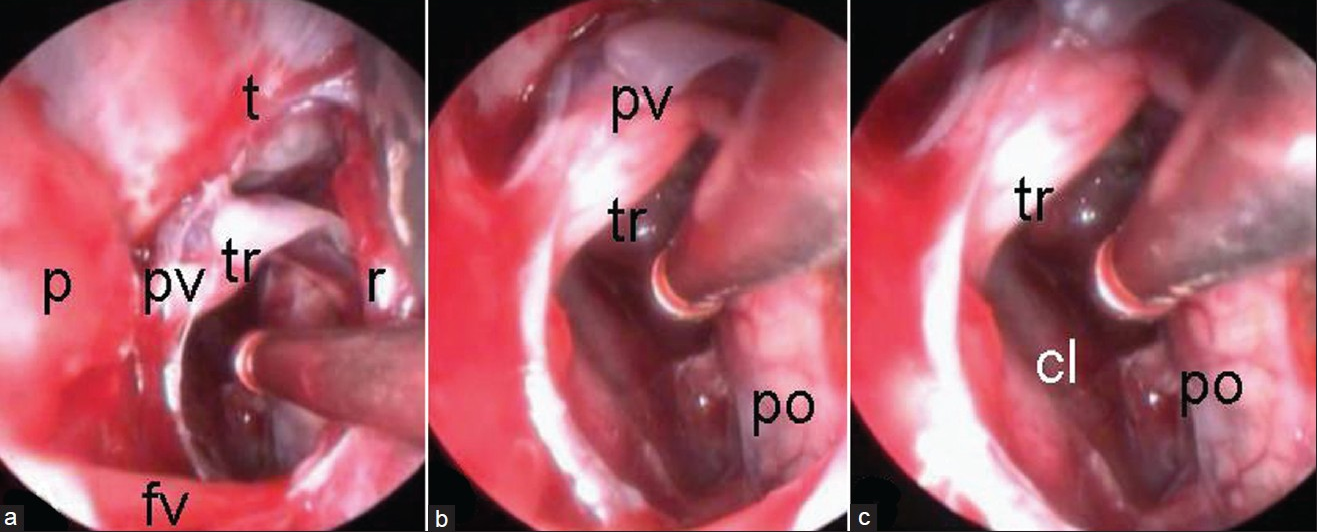

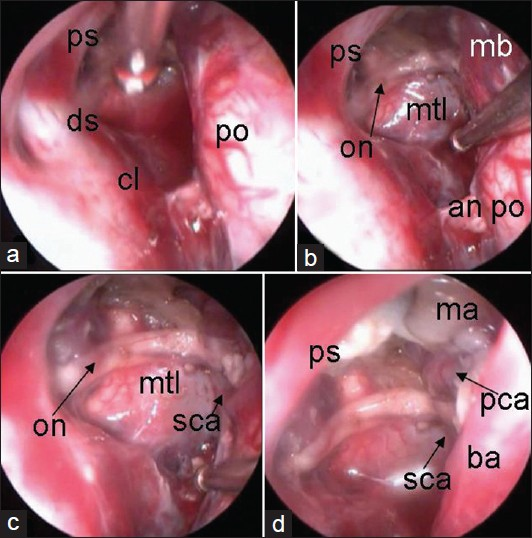

A left-sided retromastoid retrosigmoid lateral suboccipital 2×2.5 cm craniectomy was done in park bench position. Dura was opened with a retrosigmoid incision. Left-sided cerebello-pontine angle (CPA) was opened and facio-vestibulocochlear nerve complex and the tumor were identified by free hand 0° endoscope [Figures 2a and b]. A self-retaining retractor was placed to support and to open the upper CPA.The pearly white materials that confirmed the epidermoid tumor were removed near totally with dynamic free hand endoscopy and static endoscopy with endoscope holder. Petrosal vein and trigeminal nerve were entrapped by the tumor that was completely freed and preserved by careful dissection [Figures 3a–c]. Before decompression petrosal vein was identified as a small vein surrounded by tumor; after decompression it became larger. During the decompression of trigeminal nerve root, we found that a small part of tumor was deeply impinged into the nerve entry zone; extra time and very careful dissection was needed in the removal of this part of tumor. Endoscope, surgical dissector, and suction were negotiated in prepontine and interpeduncular cistern either above or below the trigeminal nerve and petrosal vein or in combination with elevation of tentorial margin. Tumor overlying the basilar artery was also carefully removed with preservation of arachnoid membrane overlying it. Abducent nerve was outside the tumor and extra arachnoidal. Opposite sixth nerve, medial temporal lobe, third nerve, superior cerebellar artery, posterior cerebral artery, upper basilar trunk, posterior part of pituitary stalk, and right mamillary body were nicely seen through the arachnoid membranes and kept intact [Figures 4a–d]. But these structures on the same side were not seen clearly even with angled (30°) endoscope. Supratentorial part of tumor was removed near totally. In the last part of surgery we used 30° endoscope to see if any residual part of the tumor was there. The vision with the endoscope was excellent. We left the small part capsule in a few places where it seemed that capsule was firmly adhering to brain stem and related structures. After dural closure bone chips were repositioned at craniectomy site.

- (a and b) Initial endoscopic view of tumor in left CP angle. fv-facial and vestibulo cochlear nerve complex; p-petrous; e-epidermoid; r-retractor; and t-tentorialcerebelli

- (a-c) Endoscopic views after removal of CP angle and prepontine portions of epidermoid (Trigeminal nerve if freed from tumor with preservation of petrosal vein). fv-facial and vestibulo cochlear nerve complex; p-petrous; e-epidermoid; r-retractor; pv-petrosal vein, Tr-trigeminal nerve; Po-pons; Cl-clivus; and t-tentorialcerebelli

- Endoscopic views after removal of supratentorial portion of epidermoid showing right-sided part of interpeduncular fossa and rightsided medial temporal lobe. (a): ps-pituitary stalk; po-pons; ds-dorsum sellae; and cl-clivus. (b): ps-pituitary stalk; mtl-medial temporal lobe; on-oculomotor nerve; mb-midbrain; an-abducent nerve; and po-pons. (c):on-oculomotor nerve; mtl-medial temporal lobe; and sca-superior cerebellar artery. (d): ps-pituitary stalk; ma-right mamillary body; ba-basillar artery; pca-posterior cerebral artery; and sca-superior cerebellar artery

Postoperative course

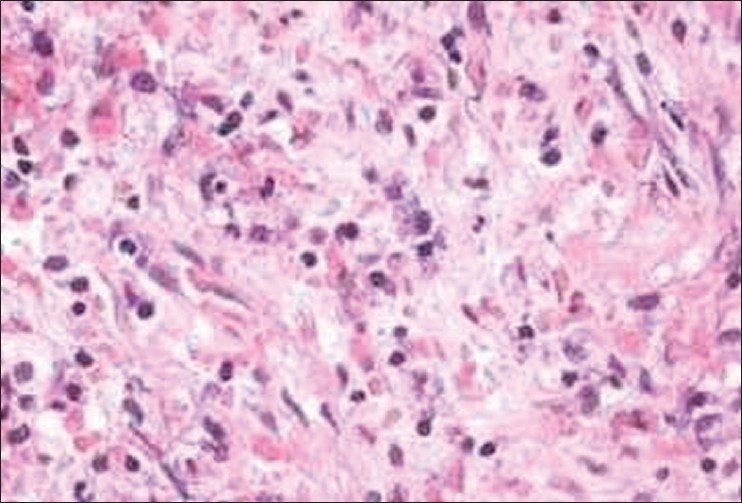

We used injection Dexamethasone and injection Phenytoin peroperatviely and postoperatively to prevent chemical meningitis and seizure, respectively. Postoperative period was uneventful. His trigeminal neuralgia was gone from the next morning of the operation. He was put on postoperative anticonvulsant for one year. Postoperative (two weeks after operation) CT scan showed reduction of hypodense area with persisted deformity of brain stem with large dead space [Figures 5a–f]. Histopathological examination of tumor tissue reported epidermoid tumor [Figure 6].

- Postoperative CT scan of brain. (a-c) axial bone window images showing craniectomy site in left retor sigmoid retromastoid suboccipital area. (c-f) axial images showing with residual dead space of tumor with distorted brainstem

- Histopathology of epidermoid: Microphotograph

Discussion

Epidermoids have a peak incidence in the fourth decade of life.[5] This so-called beautiful tumor has an irregular cauliflower-like outer surface that grows and encases vessels and nerves.[6] The cyst content is characteristically composed of a pearly white material that results from desquamation of the cyst wall. About 90% intracranial epidermoids are intradural and 7% of cerebello-pontine angle (CPA) tumors. Approximately 60% of all intracranial epidermoids occur in CPA and 15% epidermoids occur in middle cranial fossa. Spinal occurrence of epidermoid is very rare. Signs and symptoms of epidermoid cysts are due to gradual mass effect. Recurrent aseptic meningitis is uncommon but recognized complication and is similar to that of the less common dermoid cyst.Trigeminal neuralgia is not uncommon with CPA epidermoids.[7] The major differential diagnoses for an epidermoid cyst are arachnoidal cysts, hamartomatous lipomas, dermoid cysts, and cystic neoplasms.[6] They can usually be differentiated by CT scan or MRI images of brain. Conventional MR images sometime cannot reliably be used to distinguish epidermoid tumors from arachnoid cysts. In contrary, FLAIR and DW sequences can successfully be used for diagnosis of epidermoid cysts by revealing its solid nature.[8] Hydrocephalus is said to be uncommon because of the long-standing nature of the lesion and also because CSF can permeate through the crevices of the lesion. The surgical approach is generally determined by the location and the extent of the lesion. The lesion, when confined to the CPA, is approached microsurgically by a retromastoid craniectomy, whereas significant supratentorial extension needs a combined retromastoid and subtemporal approach or a staged procedure. However, the tumor commonly extends into the hiatus and this incisural part can be completely removed with the posterior fossa approach.[9] Prepontine retroclival tumors have typically been removed through a variety of anterolateral, lateral, and posterolateral cranial base approaches.[3] Sometimes endoscopic-assisted microscopic removal are useful for removal of such tumors.[2–4] Esposito et al.[3] reported two epidermoids occupying the posterior suprasellar, premesencephalic, and prepontine cisterns, with significant mass effect on the brainstem were removed endonasal transsphenoidal transclival cranial base tumor removal with the operating microscope and endoscopic assistance. One patient developed a postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak and meningitis requiring two re-operations to repair. In our case epidermoid from prepontine area and supratentorial area was removed by the endoscope with excellent vision.

In microscopic approach, visualization is limited by long, narrow surgical corridor and limited space for change of angle of vision as light source and lens are long away from the operating field. The endoscope overcomes this problem by bringing the light source and lens closer to the surgical lesion along with panoramic view of pathology and surrounding structures. Visualization provided by endoscope is outstanding and this advantage can minimize the risk of morbidity to vital neurovascular structures. In addition, because the lens and light source are at the tip of the endoscope, the endoscopic approach does not limit visibility in the lateral dimension, as occurs with the microscope. Thus, endoscope reaches to supratentorial compartment to visualize third ventricular floor, interpeduncular cistern, pituitary stalk, and medial temporal lobe. Probably it is very difficult to visualize these structures with microscope. Another advantage of endoscopic-controlled approach over a classical microscopic approaches is the avoidance of much cerebellar retraction and the possible cerebellar injury. The main disadvantage of endoscope over microscope is the absence of 3-D perception of surgical field (though 3-D endoscope is now available). In dynamic endoscopy, third surgical hand of assistant is sometimes needed for holding endoscope or for dissection. Both surgeon's hands can be used for dissection in static endoscopy where endoscope is holded by endoscope holder but still endoscope is occupying its space in the surgical road Another disadvantage of endoscopy is longer learning curve in learning endoneurosurgical skill than that of microneurosurgical skill.

There is a controversy regarding the extent of removal. Although the aim of surgery is for complete removal, few authors advocate total removal of the tumor[910] due to adherence of the capsule to the important neurovascular structures in and around the brain stem. A conservative approach with decompression and the removal of the nonadherent portion of the capsule had been suggested by others.[4] Chemical meningitis can occur by spillage of the cyst contents during operation, which usually is transient and self-limiting[9] and often responds to steroids.

Nevertheless, epidermoids are often the most troublesome to cure because of their insinuating growth into different spaces and cisterns in addition to engulfing cranial nerves and vessels which make it difficult for radical excision.[9] It is not surprising that, prior to the microsurgical era, operative mortality ranged from 20% to 57%.[4] But nowadays, surgery-induced mortality is very low, as a result of tremendous improvement in neuroimaging and microsurgical skills with endoscopic skill as well as conservative radical approach in intracranial epidermoid excision.

Partial removal of a lesion leads to recurrence after a prolonged period. As the hypodense areas revealed by CT persist for a prolonged period, even after complete removal of the tumor, possibly because of a long-standing deformation of the neural structures, a diagnosis of recurrence at an early stage is often not possible. MRI is useful to diagnose an early recurrence.[10] However, re-operation is often indicated only in the recurrent symptomatic lesion.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Endoscope-assisted microsurgical resection of epidermoid tumors of the cerebellopontine angle. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:227-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endonasaltranssphenoidaltransclival removal of prepontineepidermoid tumors: Technical note. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:E443.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical treatment of epidermoid cysts of the cerebellopontine angle. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:14-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial epidermoid cysts: Diffusion-weighted, FLAIR and conventional MR findings. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:214-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial cysts: Radiologic-pathologic correlation and imaging approach. Radiology. 2006;239:650-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidermoidtumors in the cerebellopontine angle presenting with trigeminal neuralgia. J Korean NeurosurgSoc. 2010;47:271-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative MR evaluation of intracranial epidermoid tumors by fast fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging and echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1089-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microsurgical treatment of intracranial dermoid and epidermoid tumors. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:561-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intracranial epidermoid tumors. In: Apuzzo ML, ed. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993. p. :699-88.

- [Google Scholar]